Not whether, but how fast on CO₂ storage in Norway

The following op-ed by Eivind Berstad, Bellona’s CCS team leader, originally appeared in Teknisk Ukbladet. When the European Free Trade Associatio...

News

Publish date: September 2, 2020

News

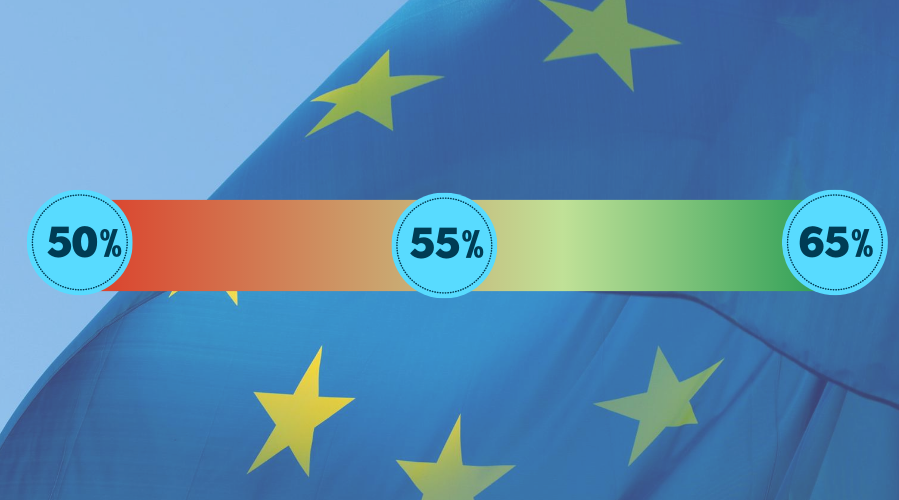

Two years deep into the EU 2030 target discussions, first launched through a quantification by the EU Commission in the immediate completion of the Clean Energy Package for all Europeans in May 2018, we have now seen 3 sets of numbers dominate the EU climate target public debate, at different times:

This higher target is currently present in the European Parliament debate as championed by the very Rapporteur of the Climate Law file, alongside other MEPs, groups as well as the wider set of climate NGOs, including Bellona (see here our response to the EU Target consultation).

As we are now approaching the much-awaited moment of a decision on a target, a question which has been answered in many ways so far, continues to beg for attention is: What’s in a target? Answering this requires first a little trip back to the basics of climate change and then a a trip back to our future. This article will provide both.

Simply put, the target is about our savings for the future. The 3 pathways for targets for 2030 presented below are based on the cumulative emissions calculations using 1851 as the starting point and the 1990 value of 243.33 GtCO2e and connect it to the final destination, the goal of a net-zero EU by 2050 (translating a core requirement of the Paris Agreement into a clear EU political goal and direction of travel for subsequent legislation). Cumulative emissions matter because climate change depends on a stock of GHG emissions in the atmosphere, to which the annual ones add to, continuously.

This is why the Paris Agreement speaks of temperature increase scenarios based on the notion of carbon budgets, which are diminishing annually, the more emissions we “spend” now. Based on this, the IPCC referred to the 2020-2030 decade as the crucial one in determining whether the world will meet its Paris Agreement targets or not.

From this scientific context, the EU 2030 target is simply the speed at which the EU plans to spend the quickly diminishing carbon budget. In other words, the target is about whether or not we will engage in economically rational behaviour with regards to our future and exercise prudence in policy-making or whether we plan to have a ‘spend-it-all’ now approach and have a sharp deep fall to the net-zero goal later on, with the implied disruptions to the system.

Behavioural economics has long strived to understand the very relationship climate advocates and policy experts try, time and time again, to explain: the idea that your spending behaviour now impacts on the savings you have left at the end of a month, year, etc. How much we spend today is as relevant for the decisions of today as it is for our remaining budget and therfore for our resilience to different economic shocks or indeed on our ability to invest in something longer-term and build bigger and better . Following the same logic, it is not a surprise to see proposals to making carbon accounting a necessary requirement for banks getting traction in the Financial Times, indicating the undeniable link between our carbon budgets and our future savings.

While economic theory seems to have drawn the line on maximising savings as constituting the basis of ‘rationality’ with regards to our economic behaviour, our climate politics seems to run in direct opposition to that, still. Less than 1 year ago, in December 2019, an assessment of cumulative emissions concluded that with the current targets in place, the world has 90% of a chance to overspend its carbon budget for limiting global warming to up to -2 degrees warming. Our unambitious EU climate targets, seem to suggest the opposite of the economic approach, in particular that spending our remaining available carbon budget now and delaying the savings for later will enable us to continue “spending” carbon as we currently do – unfortunately, climate science is rational and does not work that way.

2020 is our chance to remedy that and bring back some much needed rationality into political decision-making, which seems to be disconnected from the pressing reality of a planetary climate emergency. This is a crucial point as the EU Climate Law will need to be agreed upon in the remaining months of this year. Can the EU change this irrational approach? And if so, what exactly can the EU do?

Looking back at the 3 trajectories in Graph 1it becomes quite clear that on the scale of rationality and responsible economic behaviour, -65% would seem to rank best, while -55% would be only an acceptable, non-risk aggravating option. In fact, if we were to draw a straight line from 1990 emissions (currently the baseline for EU targets) to the goal of net-zero, we would see that indeed, 2/3 of the cuts would need to take place by 2030, in other words at least –60% on a direct trajectory to net-zero in 2050.

In addition to being about our savings and about our rationality in decision-making and planning, the EU 2030 target is clearly also about the credibility of our 2050 net-zero trajectories. A –50% by 2030 would simply leave another 50% emissions to be reduce in only two decades, after having already added up to cumulative emissions significantly. This will doubtfully convince anyone, certainly not our international partners.

There is also good news, as presented in a study released in the summer of 2020 by Climact, where see that both -55% and -65% are technically feasible and that there are in fact several options for reaching -55%, some based on accelerated technology deployment and another following a shared effort approach, including some lifestyle changes. When both approaches are combined, it is possible to reach -65% emissions by 2030 in the EU, pacing for a safe-landing to our 2050 destination.

From : Net Zero by 2050: From whether to how, Climact (2020)

From : Net Zero by 2050: From whether to how, Climact (2020)

A deeper dive into specific sectorial implications of a weak (-55%) vs. Rational (-65%) climate target by 2030 goes to show that industrial decarbonisation, similarly to some of the other more difficult to decarbonise sectors, would be pushed against a sharp cliff of declines after 2030 should there be a weaker target proposed by the EU.

From : Net Zero by 2050: From whether to how, Climact (2020)

From : Net Zero by 2050: From whether to how, Climact (2020)

A higher target would literally mean a rational approach to both lifestyle and technology development. If technologies are ready and available, why would we not seek to deploy them at scale in the next decade? Surely the cost of running out of our savings and being thrown unprepared into a future that is unpredictable will always be higher than that of investing in deploying the technologies available to reduce emissions already today and hence building up our savings with regards to our carbon budget. In an even more recent study, we see that the -55% route would also be ‘economically feasible’[1], so when rationality meets feasibility, our choices should become easier looking ahead.

So what’s in the target? Our technology, our innovation, our lifestyle and most importantly, our savings and our future jobs. Our politics must encourage us to save and to do so smartly. The Next Generation EU label of the EU Commission recover plan would best live up to its name and indeed pursue an investment path that is in line with an economically rational behaviour, that of heavily reducing emissions now, for savings in our carbon budget to last us into the future. The 2030 target discussion is not purely about numbers, but it is about whether or not our political and policy frameworks in the EU will endorse rational behaviour and guide our economy to a safe-landing. The EU has several pathways ahead and several available and feasible options – the choice is whether to embrace the rationality of savings or not.

The following op-ed by Eivind Berstad, Bellona’s CCS team leader, originally appeared in Teknisk Ukbladet. When the European Free Trade Associatio...

For the past eight years, disinformation has dominated news around elections all over the world. Despite this, it is still a widely misunderstood con...

A ruling by the European Free Trade Association Court that Norway’s continental shelf falls under the European Economic Area Agreement could dramatic...

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway