Arctic Frontiers: Disinformation, Security and the Northern Sea Route

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

News

Publish date: October 13, 2014

Written by: Anna Kireeva

News

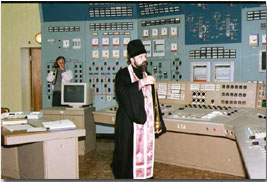

MURMANSK – In a decision vexing to environmentalists, the Kola Nuclear Power Plant (KNPP) received an engineering lifespan extension to operate its 30-year-old reactor No 4 for an additionally 25 years – giving the KNPP the distinction of operating no reactors whose original shut down date has not already passed.

The KNPP’s official website reported (in Russian) last week that Russia’s Federal Service for Environmental, Technological and Nuclear Oversight (Rostekhnadzor) had handed down approval to keep the No 4 unit online for another quarter century – until December 7 2039 – on October 8.

The website said the extension license was obtained after substantial efforts to assess equipment characteristics, followed by replacements and modernizations, and other measures directed at enhancing safety and reliability.

“The lifespan extension for the No 4 reactor was expected, but for a whole 25 years is a surprise,” said Andrei Zolotkov, director of Bellona Murmansk. “Earlier extensions [issued to KNPP reactors] were for much shorter periods of time – No one can guarantee its safe operation for another 25 years. For the moment we can only talk about 11 years of safe operation based on the example of the plant’s reactor No 1.”

Nils Bøhmer, Bellona’s managing director and nuclear physicist also voiced concern.

“To prolong the lifetime [of the KNPP’s No 4 reactor] by such a long period – almost as long as it’s design lifetime of 30 years – should not happen” he said. “When we know the processes undertaken to prolong the reactor’s lifespan occurred without an independent environmental impact study, the continued use of the reactor is a high risk operation.”

Vitaly Servetnik of the Kola Environmental Center said the extension was not only dangerous but likely illegal.

“It’s risk without necessity – the extension is illegal absent a state environmental impact study and a review of the environmental impact assessment, including public hearings,” he said.

Indeed, Russian legislation dictates that a plan for decommissioning any reactor be drawn up five years prior to the expiration of its engineered operational lifespan. But none of the reactors working well beyond their original lifespans at the KNPP have such plans on file, Servetnik said.

“The 25-year extension license handed down for reactor No 4 a few days before it reached the end of its engineers operational lifespan cannot be considered the result of any independent assessment of the reactor’s condition,” he said.

Lifespan extension record

Though all of the KNPP’s reactors are operating on extensions, none of those granted previously to reactor No 4’s received such record-breaking second leases on life.

“This is an unprecedented event in the history of Russian atomic energy,” said Vasily Omelchuk, the director of the KNPP.

The extensions received by the oldest reactors – Nos 1 and 2, which went into operation in 1973 and 1974 respectively – were granted at first for five years, and then another 10, until 2018. The No 3 reactor received a 5-year extension after 30 years of operation and is scheduled for shutdown in 2016.

Experimenting with old reactors

The KNPPs has already made known its plans to seek 15-year extensions for its two oldest reactors. If this comes to pass, these four-decade old reactors will remain in operation until 2033 and 2034 for a total of 60 years in operation. The No 4 reactor, with its new extension, will operate for 55 years. Additionally, in 2011, the KNPP received permission to experimentally run the No 4 reactor at 107 percent power. Preparations are underway to run reactor No 3 at 107 capacity as well.

“This really reminds me of the ‘process for the sake of the process’ plans adopted by [Russian state nuclear corporation] Rosatom, but it begs the question: who needs a few dozen extra megawatts when the [the Murmansk Region] has an energy surplus of about 500 megawatts, equal to the power of one reactor?” said Zolotkov.

“Rosenergoatom [Russia’s nuclear utility] lives by its own internal rules and isn’t taking into consideration territorial needs,” he said.

Zolotkov added that experiments like lifespan extensions and boosting power output are pointless because Russia isn’t going to be building any more of the KNPP’s VVER-440 reactor types.

Many VVER-440s, in fact, have been taken out of service for safety reasons. Bulgaria’s Kozloduy plant shut down its VVER 440/230s between 2002 and 2006 because the county’s candidacy for EU membership dictated it shutter Soviet built reactors as dangerous.

The Kola Nuclear Power Plant 2

Survey work for the site and construction of a second KNPP is slated to wrap up this year as well, as well as the reference reactor’s average power output (which will operate at the new plant).

“I think the actual construction of the KNPP-2, about which so much is being said and written will not under these circumstances will not happen anytime soon, and that by that time, energy parameters of the nuclear industry in the Murmansk region will doubtless change,” said Zolotkov.

“After all, we have a problem: to implement as many measures of energy efficiency as possible in the housing and public works sector by 2020 – power consumption should therefore decrease, not increase,” he said.

Who’s next in line for more energy?

The Murmansk Region doesn’t need the volume of energy it’s producing now. Nobody needs it. There’s certainly been no industrial growth in the area No one wants to buy it either: In 2012, Norway ceased buying energy from the region until the oldest reactors of the KNPP were taken out of service.

The KNPP’s 1760 megawatts of installed power in 2013 were 67 percent of the plant’s capacity, and reasons for boosting its load in the regions southern districts haven’t come along yet.

The Murmansk region has a no-less powerful hydroelectric complex, whose installed capacity in 1860 megawatts, and even that plant isn’t working at full capacity. In 2013, only 39 percent of its capacity was used.

“Everyone knows that hydroelectric power is significantly cheaper than nuclear power,” said Zolotkov. “If hydroelectric power were boosted in the Murmansk Region’s energy mix, you could lower the kilowatt hour price for consumers – but unfortunately, the KNPP is its own type of monopolist in the regional energy market and tries to dish out as much electricity as possible to support its economic performance.”

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

Our December Nuclear Digest, reported by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center, is out now. Here’s a quick taste of three nuclear issues arisin...

Bellona has launched the Oslofjord Kelp Park, a pilot kelp cultivation facility outside Slemmestad, about 30 kilometers southwest of Oslo, aimed at r...

Our November Nuclear Digest by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center is out now. Here’s a quick taste of just three nuclear issues arising in U...