New Managing Director for Bellona Norway

The Board of the Bellona Foundation has appointed former Minister of Climate and the Environment Sveinung Rotevatn as Managing Director of Bellona No...

News

Publish date: October 5, 2015

Written by: Charles Digges

News

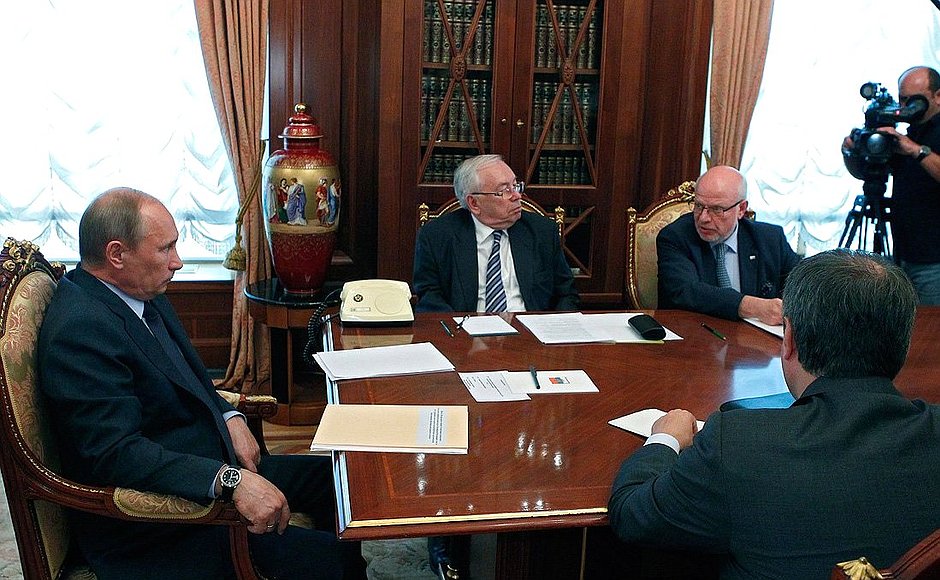

Mikhail Fedotov, the head of the Presidential Council on Civil Society and Human Rights, blasted in a meeting with Vladimir Putin the reach of Moscow’s NGO, or “foreign agent” law, which he said has tarred too many necessary organizations, the official Tass newswire reported.

The controversial NGO law that took effect in November 2012 requires non-profit organizations operating in Russia that received foreign funding and engaged in vaguely defined “political activity” to voluntarily announce themselves as “foreign agents” to the Russian Justice Ministry, and to apply the moniker to all their publications.

Apparently unimpressed by the number of NGOs who signed up to be called foreign agents – a term associated in Russian with treason – Putin in June 2014 granted the Justice Ministry sweeping powers to name foreign agents on its own. The list immediately began to grow.

The Russian Ministry of Justice. (Source: minjust.ru)

The Russian Ministry of Justice. (Source: minjust.ru)

Illegal false claims and mendacity

Last week Fedotov told Putin in an open session that environmental and human rights groups were disproportionately forced onto the Justice Ministry’s foreign agent list, and said that in numerous cases, their inclusion on the roster was, in fact, illegal.

“The attitude of several government structures to human rights groups more and more recalls a witch hunt, accompanied by false claims and mendacity,” said Fedotov in some of the strongest terms he has used to express his reservations about the NGO law to date.

His words are all the more striking, as members of the Presidential Council on Human Rights are hand selected by the president himself.

“It sufficient to glance at the roster of so-called ‘foreign agents,’ which currently already contains some 94 organizations,” continued Fedotov according to the Tass transcript. “The absolute majority of them are human rights and environmental organizations.”

Environmental groups protected by Russia’s highest court

Fedotov noted that the NGO legislation was specially written to exclude as “political activity” the labors of groups working in the defense of nature and wildlife.

Wildlife and nature preservation groups were exempted from the “political activity” clause of the NGO law by Russia’s Constitutional Court in 2014.

“I have no issues with the Ministry of Justice, they are running the roster the way it is prescribed in the law,” Fedotov told Putin. “And this proves yet again that a well-written law is a precision weapon that strikes its target dead on the mark, and a poorly written law, a law written by guesswork, is a weapon of mass destruction.”

The office of a Russian NGO defaces with the words "foreign agent."

Credit: Memorial

The office of a Russian NGO defaces with the words "foreign agent."

Credit: Memorial

Nils Bøhmer, Bellona’s executive director, was hopeful Fedotov’s forceful critique might spur a change in the Kremlin’s tack toward Russia’s non-profit sector.

“We could hope that this is a start of a process that could make the situation easier for NGO’s attacked by Kremlin in recent years,” said Bøhmer. ”Fedotov has some good arguments especially when referring to the Constitutional Court’s defense of nature conservancy.”

Absurdities that land groups on the list

Fedotov specifically cited two recent inclusions on the foreign agent list – Sakhalin Environmental Watch and the Committee for the Prevention of Torture.

The Justice Ministry tarred the Committee for the Prevention of Torture was designated a foreign agent label for so-called political activity, said Fedotov. The political activity in question? The committee’s chairman Igor Kalyapin – like dozens of other NGO chairmen – sits on Putin’s own Presidential Human Rights Council.

Sakhalin Environmental Watch was also included on the list for alleged political activities – which included the reposting to its own social media site a petition written by another group to Vladimir Putin asking him to protect the Arctic from oil spills. A further political activity committed by Sakhalin Environmental Watch was an op-ed piece written for a small paper urging regional authorities to plant more trees.

Both were seen by the Justice Ministry as attempts to interfere with the course of Russian politics.

Fedotov’s examples were trenchant but far from exhaustive. Other environmental groups have been forcibly included on the foreign agent list for equally dubious political reasons include Bellona Murmansk, Ecodefense, and Planeta Nadezhd.

Bellona Murmansk managed to plead down the 300,000 ruble fine (or $4,400 by current exchange rates) levied against it. But why was the group deemed a foreign agent?

“The Ministry of Justice thinks we are political because we’ve written that current [Russian] legislation makes it more profitable for industry to pay fines for pollution than putting in place environmental measures” to prevent pollution, said the group’s Anna Kireeva.

Ecodefense’s co-chair Vladimir Slivyak said the Justice Ministry designated his group as a foreign agent for protesting the construction of a nuclear power plant – something the Justice Ministry said was tantamount to protesting the state itself.

Instead of fighting the fines and the foreign agent designation in court, Slivyak told Bellona his group has simply chosen to refuse the demands of Russian officialdom and continue its business. So far, the civil disobedience has worked.

Nadezhda Kutepova. (Photo: wecf.eu)

Nadezhda Kutepova. (Photo: wecf.eu)

More ominous is the case of Planeta Nadezhd, whose director Nadezhda Kutepova was force to flee Russia with her three children when it became apparent Moscow might charge her with treason.

Her group worked to protect the rights of victims of radiation accidents in her small closed nuclear town, Ozersk, where Russia’s notorious Mayak Chemical Combine is located. Planeta Nadezhd was forced onto the foreign agent list in June for receiving a foreign grant in 2008 – four years before the NGO law took effect.

She was further targeted for remarks she made in a June 2014 interview with Bellona’s Russian-language news pages in which she presented the radiation dangers still facing residents of the Chelyabinsk Region, where Ozersk is located.

Kutepova began dissolving it rather than pay fines she couldn’t afford. She is the first representative of an NGO called a foreign agent who has been forced to flee Russia. She is seeking political asylum in France.

Financed or not, human rights groups are needed

In his remarks to Putin, Fedotov took up the issue of foreign financing as well.

“Some NGOs have been excluded from the foreign agent list, but what has changed in their work after they began refusing foreign funding?,” he said. “Well, nothing unless we consider reduced staff and salaries for their employees.”

Fedotov said that “for real human rights advocates, foreign grants are not the end, but rather the means for fulfilling their missions – if there are domestic grants, then thank you – NGOs will continue their work on Russian funding, and if there’s no funding at all, they’ll continue to function on a volunteer basis.”

Fedotov went further, saying those charged with monitoring NGOs do so “by their own yardstick” and “when they find they have nothing in common with them, demonize them.”

“In fact, human rights advocates,” said Fedotov, “are the foremost helpers to those in power in the business of building a rights-based government.”

The Board of the Bellona Foundation has appointed former Minister of Climate and the Environment Sveinung Rotevatn as Managing Director of Bellona No...

Økokrim, Norway’s authority for investigating and prosecuting economic and environmental crime, has imposed a record fine on Equinor following a comp...

Our op-ed originally appeared in The Moscow Times. For more than three decades, Russia has been burdened with the remains of the Soviet ...

The United Nation’s COP30 global climate negotiations in Belém, Brazil ended this weekend with a watered-down resolution that failed to halt deforest...