Not whether, but how fast on CO₂ storage in Norway

The following op-ed by Eivind Berstad, Bellona’s CCS team leader, originally appeared in Teknisk Ukbladet. When the European Free Trade Associatio...

News

Publish date: May 12, 2020

News

By 2030, the Russian government will raise seven pieces of radioactive debris – including two nuclear submarines – from the bottom of Arctic oceans, where they were intentionally scuttled during the Soviet era, documents received by Bellona confirm.

The documents identify this debris as the most dangerous of the items the Soviet Union discarded in polar waters, and say that six of them contain more than 90 percent of the radioactivity to be found on the Arctic seabed.

Of particular importance, the documents say, are the K-159 and K-27 nuclear submarines, the nuclear reactors of which were still full of nuclear fuel when they went down.

Both submarines, say experts, are in a precarious state. In the case of the K-27, which was scuttled intentionally in 1982, the sub’s reactor was sealed with furfural, before it was sunk. But experts say this seal is eroding. The K-159, which sank while it was being towed to decommissioning in 2003, poses similar threats. Some 800 kilograms of spent nuclear fuel remained in its reactor when it went down in some of the most fertile fishing grounds in the Kara Sea.

In both cases, experts fear that a nuclear chain reaction could occur should water leak into the submarines’ reactor compartments.

Russian scientists have kept a close eye on the K-159, launching regular expeditions to monitor for potential radiation leaks. According to their data, should the submarine depressurize, radionuclides could spread over hundreds of kilometers, heavily impacting the local fishing industry.

Anatoly Grigoriev, who heads up the international programs department of Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear corporation, says that raising the wrecks will cost some €123 million.

“Should the K-159 depressurize, it could cause €120 million of damage per month,” Grigoriev told Bellona at an earlier meeting.

The documents in Bellona’s possession indicate that, between 1959 and 1992, the Soviets carried out 80 missions to sink radioactive debris at sea. In total, some 18,000 objects considered to be radioactive waste were plunged to Arctic depths. Aside from the K-159 and the K-27, the Soviet Navy scuttled reactor compartments, solid radioactive waste, a number of irradiated vessels, as well as old metal structures and radioactive equipment.

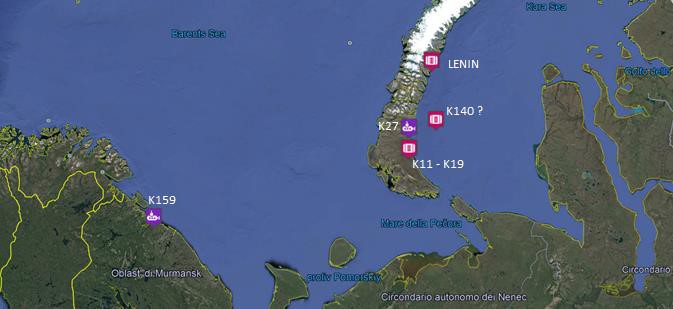

A map showing the locations of radioactive debris sunk by the Soviet Navy. This includes the K-27 and K-159 submarines, as well as the reactor compartments from the К-11, К-19, and К-140 submarines, as well as waste from the Lenin nuclear icebreaker.

A map showing the locations of radioactive debris sunk by the Soviet Navy. This includes the K-27 and K-159 submarines, as well as the reactor compartments from the К-11, К-19, and К-140 submarines, as well as waste from the Lenin nuclear icebreaker.

The majority of this debris was left in the eastern bays of the Kara Sea near the Novaya Zemlya Archipelago. Still, the exact location of some of these sunken objects is still unknown. The whereabouts of the reactor compartment from the K-140 nuclear submarine remains unaccounted for.

And there are other radiation hazards that are farther afield. The K-278, or Komsomolets, nuclear submarine lies at the bottom of the Norwegian Sea.

“A quarter of all the radioactive waste that has been sunk in the oceans belongs to us,” says Sergei Antipov, director of strategic planning and project management at the Nuclear Safety Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Since the early 2000s, massive projects to decommission Soviet-era nuclear submarines have been ongoing with the assistance of numerous western partners. Moscow has shared information about these radioactive hazards with nations of the G-7 and has worked with the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development and other donors.

This international cooperation has brought significant results. Military bases have been cleared of most radioactive contamination and nearly 200 rusted-out nuclear submarines have been safely dismantled, as a review of the last 25 years of Bellona’s work clearly shows.

Russia, moreover, has the necessary infrastructure to deal with whatever discarded radiation hazards are brought to the surface of Arctic waters. And while Russia lacks the necessary vessels for such undersea rescues, the international partners it has developed while cleaning up other pieces of the Soviet nuclear legacy certainly do.

Next year, Russia assumes the rotating chairmanship of the Arctic Council, and we hope that Moscow will be able to announce upon the first meeting that these projects are underway. Bellona, which is already involved in discussing this important work, has high hopes.

The following op-ed by Eivind Berstad, Bellona’s CCS team leader, originally appeared in Teknisk Ukbladet. When the European Free Trade Associatio...

For the past eight years, disinformation has dominated news around elections all over the world. Despite this, it is still a widely misunderstood con...

A ruling by the European Free Trade Association Court that Norway’s continental shelf falls under the European Economic Area Agreement could dramatic...

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway