Court decision puts Norway on the hook for massive CO₂ Storage build-out

A ruling by the European Free Trade Association Court that Norway’s continental shelf falls under the European Economic Area Agreement could dramatic...

News

Publish date: December 19, 2014

Written by: Andrey Ozharovsky

News

ANGARSK, Irkutsk Region, Russia—The Russian uranium enrichment enterprise Angarsk Electrolysis Chemical Combine (AECC) admitted at a public hearing in early December that radioactive waste containing uranium, transuranic elements, and uranium fission products are in storage at its “Site 310.” But with no detailed plan about what to do next with the waste, the facility and the waste’s future remains under debate.

The public hearing was convened in Angarsk, Irkutsk Region in Southwestern Siberia, on December 5 to discuss the Environmental Impact Assessment report for the proposed project of decommissioning the storage facilities of Site 310 – which will require relocating the waste contained inside them, with, so far, no specific address available for where to send it.

Representatives of environmental NGOs who were present and spoke at the hearing voiced their opposition to removing the waste from storage before a definitive decision on how the waste would further be handled was made.

What remains undetermined is whether the waste would be placed for temporary storage elsewhere on the combine’s territory or transferred into the purview of either of the State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom’s two radioactive waste managing entities: RosRAO, which handles processing and temporary storage of low- and medium-level radioactive waste, or the newly created National Operator for Radioactive Waste Management, which was formed to work out final disposal solutions for Russia’s radioactive waste stockpiles.

The Environmental Impact Assessment report was thus sent back for further review.

The hearing, scheduled during work hours, lasted less than an hour and a half. Some 150 participants were present. The report itself (in Russian) – a copy of which Bellona obtained prior to the hearing – is only fifteen pages long, and provided little to no understanding of what kind of waste is at issue or what its fate is presumed to be.

The document stated simply that the purpose of Site 310 is “temporary storage of process waste from sublimate production” – referring to the production of uranium hexafluoride, which at the temperature of around 57 degrees Celsius is transformed from a solid material to a gas, a process called sublimation. The uranium hexafluoride gas is then used in the AECC’s centrifuges for uranium enrichment. Uranium, enriched in the uranium-235 isotope, can be used to manufacture nuclear fuel for various reactor types. (It was earlier reported, however, that a decision had been made to cease uranium hexafluoride production at the enterprise starting April 1 this year, owing to the line “not loaded to full capacity.”)

Though the document described the site’s parameters and history in detail, it offered no information on the exact quantity, chemical and isotopic composition, or activity levels of the waste in storage. Bellona’s calculations based on the data on the site’s storage capacity and use of storage space, provided in the report, suggest some 7,000 cubic meters of waste are in storage. This is enough to require over a hundred standard railway cars for removal – that is, if this kind of material could just be heaped in bulk into standard cars for transportation. Many more would be needed for safe transportation in special-purpose containers.

It was at the hearing in Angarsk that the AECC’s Site 310 was revealed to have in storage radioactive waste containing uranium, transuranic elements, uranium fission products representing process waste from manufacturing uranium fluoride compounds, contaminated equipment, and spent sources of ionizing radiation.

The AECC proposes removing the waste from the reinforced-concrete underground reservoirs where it is held, but there is no clarity with what happens to it next: The document presented no specific plans to transport the waste from the territory, nor plans to build a surface facility to provide it with temporary residence.

The environmentalists present at the hearing called for a more responsible approach and an elaborate plan accounting for all the waste management steps from the moment of removal to the moment of placement in a temporary storage facility or an internment site. The NGO representatives’ proposal was to put the project on hold until a clear decision on what to do with the waste was made.

Openly and without bias

Angarsk Deputy Mayor Alexander Lysov, who chaired the meeting, said in his opening remarks that the Angarsk municipal administration’s goal while conducting the hearing was to ensure the openness and availability of the documents brought forward for discussion and to uphold the principle of impartiality.

This goal was only patchily achieved: The AECC representative at the hearing declined to answer some of the questions.

To the deputy mayor’s credit, he delivered on his promise of an “impartial conducting of the hearing.” Everyone who wished to say something was given an opportunity to do so. Questions were allowed both in written form and by simply speaking from one’s seat in the audience. Taking the floor, too, was allowed for those who were in the audience without applying in advance to be included on the speaker list.

Still, getting the AECC representative to answer all the questions asked proved beyond the deputy mayor’s powers. But as the Environmental Impact Assessment report was in the end returned with a proposal for additional review, and the documents that were discussed will have to undergo significant changes, a new and improved report will likely be presented again for a new public hearing or round table discussion in Angarsk.

The uranium and transuranium elements

The intrigue of the hearing pivoted on the question of what exactly is stored at Site 310 – as the report failed to specify what sort of waste it is or whether it is even radioactive waste. Alexander Derzhavin, a senior specialist at the AECC’s capital construction department, and the only speaker with a presentation to deliver at the hearing, during his twenty-minute speech never referred to the storage facilities’ contents as “radioactive waste.” Instead he used a variety of euphemisms, including “process waste,” “sublimate production waste,” etc., even though he mentioned several times the need to ensure radiation safety, radiological monitoring, and decontamination of structures.

One can only speculate as to why Rosatom would be at such pains to avoid mentioning, both in the Environmental Impact Assessment report and during the public hearing, that there is radioactive waste at the site.

In a written address (in Russian) that he read during the hearing, Alexander Kolotov, who chairs the Krasnoyarsk branch of the democratic party Yabloko’s ecological faction Green Russia, suggested that such reticence was intentional in order “to take this project out of the jurisdiction of the Federal Law of the Russian Federation of July 11, 2011 No. 190-FZ ‘On the Management of Radioactive Waste’ and the purview of the National Operator for Radioactive Waste Management.”

During the hearing, the AECC representative admitted that the combine does not have a license for long-term storage of radioactive waste, which presumably adds water to Kolotov’s theory.

It was not until the Q&A session that the waste under discussion was confirmed to be, in fact, radioactive waste. On the eve of the hearing, the Angarsk newspaper Vremya asked a series of questions, including: “What is the volume, mass, chemical composition, isotopic composition, and the specific and total radioactivity of the waste contained in the storage facilities of Site 310 proposed for decommissioning?”

The AECC’s Derzhavin gave the following answer to that question:

“Site 310 holds process waste in the solid physical state. According to record-keeping data, the total mass of the waste is 1,910.97 tons. The total volume is 1,942.5 cubic meters. As regards the chemical composition, the waste is presented as a mix of fluorides, oxides, and carbonates of natural isotopes of uranium. Besides uranium isotopes, the radioactivity of the waste is due to the presence of transuranic and fission elements. The average uranium content in the process waste does not exceed 1 percent.”

What was left unanswered was the question about the total and specific radioactivity of the waste, and that is the kind of information that is pertinent to waste classification – and hence, further handling – under the existing law. For instance, Russian Federation Government Decree No. 1069, of October 19, 2012, “On the criteria of classifying solid, liquid, and gaseous waste as radioactive waste, the criteria of classifying radioactive waste as special radioactive waste and removable radioactive waste, and the criteria of classification of removable radioactive waste” – the difference between “special” and “removable” waste being the availability of methods to remove the waste safely from its location for further treatment and disposal – states that solid waste containing natural alpha-emitting radionuclides, such as uranium, is classified as radioactive waste if the nuclides’ specific activity exceeds 1 becquerel per gram.

Likewise, the isotopic composition of the waste remains unknown. No information was made available on the composition of the spent sources of ionizing radiation in storage at the site. No clarity was provided to the question of which transuranium elements exactly are present in the waste. As transuranium elements are not found in natural uranium, it stands to reason that the AEСС’s operations involved reprocessed uranium, possibly of foreign origin. The presence of transuranic elements such as plutonium, neptunium, or americium, would make the waste that much more dangerous and difficult to handle.

Besides, the information presented at the hearing is at odds with the combine’s environmental safety report, which states that “radioactive waste is generated as a result of processing raw material of natural origin, composed only of natural uranium radionuclides.”

As some of the important questions were left unanswered, the hearing failed to provide all the necessary details about the radioactive waste the AECC plans to remove from the site.

State of the storage facilities

Derzhavin, of the AECC, somewhat elaborated on the categories of waste held in each of the nine storage facilities of Site 310.

The storage project was developed in 1958, according to the Environmental Impact Assessment report, and first waste was placed there in 1961. Seven of the facilities (types A and B) are cylinder-shaped solid-cast reinforced-concrete reservoirs, with the largest five of them having a diameter of 24,88 meters, a height of 4,5 meters, and a holding capacity of 2,000 cubic meters. Another (type C) is represented by two rectangular reinforced-concrete trenches with a length of 22 meters long, combined width of 10 meters, and height of 3 meters, and a capacity of 300 cubic meters each. The smallest (type D) is a reinforced-concrete cube with a holding capacity of 10 cubic meters (2 meters in length and width, 2,5 meters high). All but three reservoirs are now filled to project capacity.

In the type A facilities, Derzhavin said, there are contaminated construction materials and spent sources of ionizing radiation; the type B facilities hold uranium-containing process waste from the production of uranium fluoride compounds, slag left from pyrometallurgical decontamination of ferrous metal waste, again spent sources of ionizing radiation; the type C storage holds uranium-containing process waste from the production of uranium fluoride compounds and contaminated equipment parts; and the type D facility, spent sources of ionizing radiation.

It remains unclear why storage of all spent sources of ionizing radiation, which contain certain very hazardous radionuclides, was not arranged separately, in the special type D facility, and for what purpose some of them were placed in mixed storage with the process waste. Such an arrangement will complicate sorting of the waste and may increase exposure for the personnel who will be engaged in decommissioning the site.

Why decommission in the first place? The Environmental Impact Assessment report states that the facilities are in “limited working condition,” and “dismantling Site 310 is recommended.” It could also be that due to the cease of uranium hexafluoride production, generation of new waste in need of storage is not expected in the future.

The document describes the state of the facilities and lists a number of defects: certain characteristic damage and cracks indicating unequal settlement of the structures and risks to the facilities’ structural stability.

Responding to questions about the facilities’ subsidence, the size of cracks, and other defects in the structures, Derzhavin said: “A quantitative assessment of the differential settlement of the structures is practically impossible to carry out without removing the bunding and unloading the waste. The assessment of the differential settlement and other defects has been done using the indirect signs – formation of cracks. [The structures of the storage facilities] show part-through thread-like vertical cracks up to 1.5 meters in length and up to one millimeter in opening. All the facilities of Site 310 are equipped with external and internal waterproofing as per project requirements.”

According to the AECC’s data, no leaks from the site have been detected so far. “In order to control the condition of the site for temporary storage of the AECC’s waste, groundwater monitoring is conducted using a network of observation wells. Observation results of the last 10-15 years confirm absence of leaks or penetration of radionuclides into the environment, which also testifies to the reliability of the storage facilities’ waterproofing,” Derzhavin said.

According to Derzhavin, the condition of the structures does not present a threat, and there is no reason to expedite the decommissioning process, even though the combine does not have data on the precise damage the structures have sustained over the years. At the same time, the presence of cracks may contribute to formation of new cracks and further deterioration of the structures. And taking the severe Siberian climate into account, even hairline cracks, should they take in water – for instance, as a result of condensation due to temperature fluctuations – may lead to increased corrosion in the concrete, but neither the Environmental Impact Assessment report, nor the presentation given at the hearing mentioned such risks.

In response to a question asked by the Balakovo branch of the Pan-Russian Nature Conservation Society (in Russian), the AECC’s representative said: “The site has not been allowed to decline to a near-accident condition. It performs its functions. We could either do radical repairs and continue storing, or combine two things – unload the radioactive waste and close the storage facilities, so that it would be impossible to fill them with any new waste.”

Storage facilities to be ‘liquidated,’ waste placed in containers

“Filling of the storage facilities was stopped in 2011 due to the passing of the law ‘On the Management of Radioactive Waste.’ This site holds waste that is federal property,” Derzhavin said at the hearing.

The AECC’s representative added that the nine underground storage reservoirs of Site 310 are planned to be decommissioned according to what is called the “liquidation” scenario: Each of the facilities will be opened one by one, and the radioactive waste stored in each will be extracted and packed into containers. The extraction operations will be “seasonal,” i.e., they will take place during the warm season of the year.

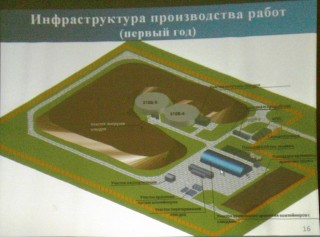

According to Derzhavin, the extraction of waste from all the facilities is expected to take four years. This is how the AECC’s representative described the works planned for the first year: “The structures’ bunding is removed. The necessary infrastructure with a radiation-monitoring station and a sanitary control station is built. Access to the facility is gained by opening the side surface. Ventilation, water treatment systems are installed. In the course of the season, all the waste in the facility is reloaded into special containers. During the loading into the containers, the waste undergoes [inventorying], decontamination, and [is then shipped] to a specialized organization for further reprocessing, conditioning, and internment.”

The idea to empty the waste-filled underground facilities by cracking open the concrete sidewalls – rather than through the roof – sounds odd. But that is not the main problem with the plan. What remains the main problem is that the project presented at the hearing goes only as far as extracting the waste – and offers no specifics as to what happens with the waste next.

Nowhere to ship, nowhere to store

Answering a question asked by the local newspaper Vremya, Derzhavin said:

“The waste from Site 310 is expected to be shipped to a specialized organization that has the necessary waste management license for reprocessing, conditioning, and subsequent internment at final disposal sites in accordance with the legislation on the use of atomic energy. The particular specialized organization is determined in the course of a tender in accordance with the Unified Industry Procurement Standard of the state corporation Rosatom. The internment site is to be determined by the one legal entity that is specified by the [government], the National Operator [for Radioactive Waste Management].

Still, Derzhavin did not elaborate – even after a series of direct questions – on any contracts either with the National Operator or RosRAO, nor on any preliminary agreements with these or any other organizations.

To Bellona’s remark about the need to bear responsibility for the entire chain of management the waste planned to be extracted from the storage facilities will go through, Derzhavin said: “The given project provides for the procedure of packing [the waste] into containers and transferring [it] to a specialized organization. Beyond that, the chain of [waste management] activities is not resolved today, and everyone understands that!”

“A network of organizations has been created that are licensed for temporary storage of waste,” Derzhavin went on. “Temporary storage of waste is carried out until the National Operator solves the problem of final disposal. This given project does not cover the entire [waste management] chain and cannot do so! The AECC must at this time receive the license so as to have the possibility, in the future, in order to solve the issue, to start the work of liquidating this site. If these issues do not get solved, the AECC will be maintaining these facilities in working order and will continue to provide temporary storage of the collected waste.”

Vyacheslav Ivanets, a member of the Angarsk Regional Duma, spoke almost at the close of the hearing, saying the waste storage facilities at the AECC were a ticking bomb.

“The waste must be taken away from the Angarsk area,” Ivanets said, “but if there is nowhere to ship it, then there is the danger that it still will remain here in temporary storage.”

Derzhavin replied by saying that the combine has no possibility of temporary storage. “For that, we need to build a new storage facility. If we want to build [a new temporary storage facility], there’ll be the same procedure – a state environmental assessment and a public hearing.”

In other words, the AECC representative assured the gathering that should the approach to the further handling of the waste from Site 310 change, the public will be informed of it.

The entire waste management chain must be clearly determined

So, the AECC wishes to rid of the waste accumulated over the years of its operations. This is understandable. But the question remains whether moving the waste could be done today with the resources the combine – and the industry as a whole – have at their disposal.

Will extracting the waste from the facilities – which are not, in the AECC’s assertions, in critical condition – entail increased radiation risks? And, with no permanent disposal site yet ready to take the waste from Angarsk – Russia at present has no internment sites aside from a number of locations where liquid waste is pumped into deep geological formations – and no clear final disposal plans set for this waste, if no new surface storage facility is planned for construction to accommodate it after its removal, then storing it in less-than-appropriate conditions could take dozens of years before a definitive decision is made. As they say, there is nothing more permanent than a temporary solution.

The nuclear industry must bear the whole weight of responsibility for the radioactive waste generated as a result of its activities. But one must not hurry with offering solutions even in the case of a small storage site that Site 310 is. A comprehensive concept is needed that will be grounded in clear understanding of what will be happening with the radioactive waste from Site 310 at every step of the way after the extraction stage. Well-thought-out planning is needed with regard to the location of the final disposal site, the delivery route and methods, and the methods and conditions of storage or internment. In other words, responsibility must be taken for the entire waste management chain that this waste will go through. The idea of extracting the waste without guarantees that there will be the possibility to completely ensure its safety after removal makes for an extremely near-sighted approach, if not an irresponsible one.

“The AECC is proposing what may not be the best way to spend 1.7 billion roubles in the [current] crisis: simply dig out the radioactive waste from the underground storage facilities to the surface without the guarantee of its further safe internment. There may not be either the location or the funds for its disposal at a new site,” Marina Rikhvanova, head of the environmental NGO Baikal Ecological Wave, told Bellona. “And the depleted uranium hexafluoride, completely abandoned, is still there, stored in containers in the open air – that problem, I would say, is more urgent. We would suggest to Rosatom organizing a joint forum in Angarsk on the future of the AECC – developing new industry [in the area], working out a strategy to manage the waste.”

As he adjourned the hearing, Angarsk Deputy Mayor Lysov proposed that the Environmental Impact Assessment report be sent back for further work and, as it was being improved, that “the comments and proposals put forward during the hearing be in due order taken into account.”

What should be done with the waste is at the moment unclear, but clearly, the discussion of the future of Site 310 and the AECC’s other radioactive waste storage sites must continue. So, after the additional work is done on the document, expanded and improved, it should be published anew and discussed anew with the public.

A ruling by the European Free Trade Association Court that Norway’s continental shelf falls under the European Economic Area Agreement could dramatic...

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

Our December Nuclear Digest, reported by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center, is out now. Here’s a quick taste of three nuclear issues arisin...

Bellona has launched the Oslofjord Kelp Park, a pilot kelp cultivation facility outside Slemmestad, about 30 kilometers southwest of Oslo, aimed at r...