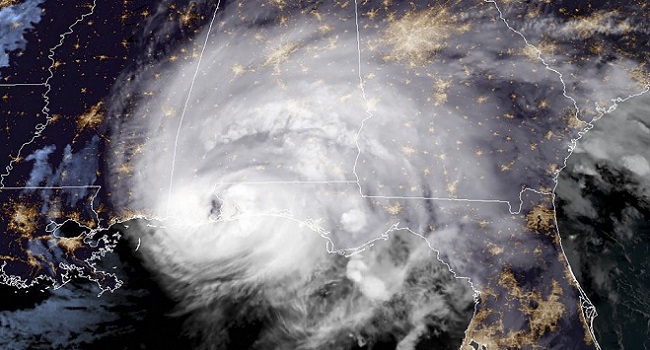

Hurricane Sally, a slow-moving system pregnant with rain, finally made landfall on Wednesday, battering America’s Gulf Coast with floods and wind while the West Coast burned, representing what scientists say is a one-two punch from climate change.

Hurricane Sally, a slow-moving system pregnant with rain, finally made landfall on Wednesday, battering America’s Gulf Coast with floods and wind while the West Coast burned, representing what scientists say is a one-two punch from climate change.

Sally’s outer bands unleashed relentless rain that began Tuesday and continued unabated through the night into Wednesday, deluging communities from Florida to Alabama and Mississippi. Meteorologists were stunned by its slow progress as the storm limped forward at a mere 3 kilometers an hour, shifting erratically in its path and intensity. As recently as Monday, the storm had been forecast to hit New Orleans, before taking a freak eastward turn.bel

Scientists observing Sally’s stall over the warm waters of Gulf of Mexico say the storm is yet another sign of climate change’s assault on America, coming as wildfires stretching from California to Washington state have consumed hundreds of communities and sent an estimated 110 million tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere – equivalent to the annual emissions of the entire UK power sector. A long, dry summer, made worse by the burning of fossil fuels, have made the continuing wildfires the worst on record.

All of this amid a hurricane season that has been among the busiest ever observed. Hurricanes have formed so rapidly this year that there is now only one name – Wilfred – left on the 21-name list that meteorologists use designate storms each year.

“Considering we are at 20 named storms now — we’re just barely past the halfway point of the season — that’s a lot,” Dennis Feltgen, a spokesman and meteorologist with the National Hurricane Center in Miami, told The New York Times. “We still have two and a half months of the season to go.”

So far, the only season that has produced more storms was 2005 – the one that gave us Hurricane Katrina – which topped out at 28. But that record may be broken soon enough: This week has seen the National Hurricane center in the US identify five simultaneous hurricanes and tropical storms in the Atlantic – for only the second time on record. When then names run out, meteorologists will turn to the Greek alphabet to designate the storms.

Hurricanes are also slower and wetter – a fact that scientists say are the ear markings of climate change. A study published in Nature in 2018 shows that between 1949 and 2016, the forward speed of all hurricanes and tropical storms has slowed by some 10 percent. Another study from that year that researched only Atlantic Hurricanes found that storms there have slowed by as much as 15 percent.

Other recent research, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, suggests that global warming, especially in the Arctic, is weaking atmospheric circulation, which also seems to be making hurricanes more sluggish. And as the air warms up, it holds more vapor, James Kossin, an atmospheric research scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information, told CNN.

By Thursday, all of what that research says was apparent on the ground in places like Pensacola, Florida and Gulf Shores, Alabama, where storm surge and relentless precipitation from Sally ran rivers of water through streets, waterlogging entire communities. Barges came unmoored from their docks, battering bridges, and roads became unpassable, blocked by downed trees, debris and fallen power lines.

In all, Sally’s sluggish progress led to staggering rain total, with 61 centimeters measured in some areas by midmorning Wednesday and a two-meter surge of seawater blown into coastal communities, driven by 165-kilometer-an-hour winds.

When it was over, nearly 400 people had been plucked by rescuers from flooded areas, the Associated Press reported – including a family of four had taken refuge in a tree.

This phenomenon of stalled storms is no longer new.

Last year, Hurricane Dorian raked the Bahamas for a day and a half, wreaking widespread destruction and pushing storm surge over the island. Hurricane Harvey, which hit Houston in 2017, is the best known – and most expensive – example of stalling. While Harvey was downgraded to a tropical storm when it came ashore, it still inundated the city with a meter and a half of water that poured for several days.

Still, Hurricanes aren’t the only kinds of storms that are affected by climate change – and not the only sort of storm that can bring catastrophic flooding to the Gulf Coast and other regions. Record rain from a low-pressure system in August 2016, a large storm but one that did not rotate like a hurricane, led to floods in Southern Louisiana. A gauge east of Baton Rouge, the state’s capital, measured 67.3 centimeters of rain in just three days.

That storm prompted an attribution study, research that tries to determine the extent, if any, of climate change’s influence on an extreme weather event. It found that climate change had increased the likelihood of such a storm along the Gulf Coast in any given year by 40 percent since 1900.

“The risk of extreme precipitation events in this region has gone up,” Sarah Kapnick, a researcher at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, N.J., who worked on the study, told the Times.

“So when you get these storms, be they hurricanes or summer storms, they have the potential to hold more water in them,” she added. “And that water has to go somewhere.”

Meanwhile, far out in the Atlantic, Teddy became a hurricane Wednesday with winds of 160 kilometers per hour. Forecasters said it could reach Category 4 strength before closing in on Bermuda.