Arctic Frontiers: Disinformation, Security and the Northern Sea Route

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

News

Publish date: November 5, 2018

News

Russia’s floating nuclear power plant, long a controversial dream of the country’s atomic energy industry, has finally become an actual nuclear power plant after its first reactor achieved a sustained chain reaction at its mooring in Murmansk harbor last week.

The news came in a release to RIA Novosti, a semi-official Russian newswire, which on Friday quoted an unnamed official with Rosatom, Russia’s state nuclear energy enterprise.

“The physical launch of the reactor unit on the starboard side of the floating power plant Akademik Lomonosov occurred on Friday,” the official was quoted as saying.

“The reactor unit reached the minimum controlled power level at 17:58 Moscow time.”

A series of reactor tests will now follow, according to the official, and the second reactor on the port side of the nuclear barge will be brought to minimum power in the coming days.

After the reactor tests, the Akademik Lomonosov will be towed through the Arctic to the far eastern Siberian port of Pevek, a town of 100,000 people in Chukotka, were it is slated to go online in the summer of 2019. The plant is expected to replace the energy supplied by the Bilibino nuclear power plant – the world’s four northernmost commercial reactors – which Rosatom will begin decommissioning in 2021.

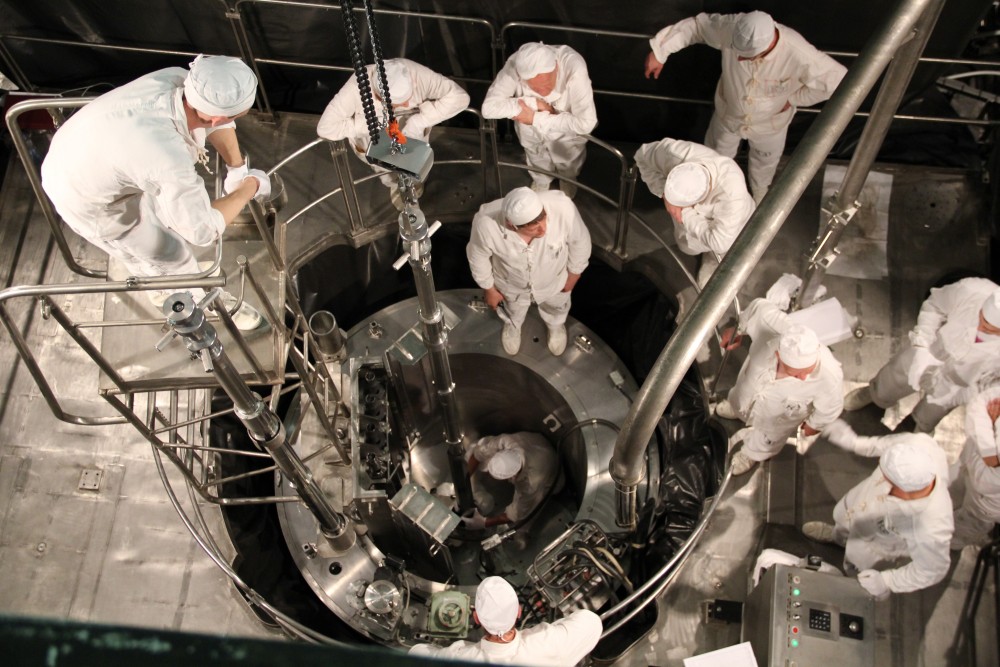

Technicians loading the first reactor aboard the Akademik Lomonosov, Russia's floating nuclear power plant.

Credit: Rosenergoatom

Technicians loading the first reactor aboard the Akademik Lomonosov, Russia's floating nuclear power plant.

Credit: Rosenergoatom

For 12 years Russia has been pursuing its audacious experiment in floating nuclear power, fording a river of doubt, economic downturns and environmental outcry – and confounding critics who said the plant was an expensive publicity stunt that was doomed to failure.

Despite dodging such predictions, the plant remains as improbable as ever – a huge, ungainly nuclear solution in search of a problem.

Since its rocky – and often secretive – beginnings in the early 2006, Russia has attempted to sell the plant as a cure-all for energy woes in the world’s more remote regions.

And while the plant has spawned a number of imitation plans in other countries it has failed to draw the windfall of orders Rosatom said would justify its $480 million cost. Rosatom officials themselves have conceded that this price tag is too high to bring the floating plant, as designed now, into serial production.

Yet the corporation has done much in recent months to draw back the veils of mystery it draped over the plant through much of its construction. The apprehensive eyes of the world’s media were upon the plant last April when it was finally towed into the open ocean from St Petersburg’s Baltic Shipyard en route to Murmansk.

Bellona's Oskar Njaa in the control room of the Akademik Lomonosov.

Credit: Bellona

Bellona's Oskar Njaa in the control room of the Akademik Lomonosov.

Credit: Bellona

In October, Rosatom invited Bellona to be the first foreign environmental group to inspect the Akademik Lomonosov at its moorings at Atomflot, Russia’s Murmansk-based nuclear icebreaker port.

Still, the new openness has done little to settle Bellona’s central concerns about Rosatom’s long-range intentions for its floating nuclear power plant. By design, the plant is meant to operate in remote regions. But this very remoteness, Bellona has said, would vastly complicate the rescue operations that would be necessary after an accident, as well as the more routine clearing of spent nuclear fuel from its reactors.

Likewise, visions of Fukushima’s waterlogged reactors have not faded from public memory, and the thought of a nuclear power plant as vulnerable to tsunamis and foul weather as is the ocean-based Akademik Lomonosov strikes an anxious chord among environmentalists.

Rosatom has often said the plant is invulnerable to tsunamis, and cite the fact that its water-borne location will give it access to infinite supplies of reactor coolant in the event of an accident.

But environmentalists are skeptical. In the worst-case scenario, the plant might not ride out the waves, but instead be torn from its moorings to barrel inland through buildings and towns until it lands, battered and breached, with two active nuclear reactors on board – well away from its source of emergency coolant.

Rosatom’s best option in that disaster scene would be the 24-hours worth of backup coolant located aboard the barge, which is hardly reassuring.

Still, the whole idea of a floating nuclear plant has piqued curiosity – and competition. Two state-backed companies in China are said to be pursing plans for at least 20 floating nuclear plants, and American scientists have drawn up blueprints of their own.

The company estimates each floating plant will take four years to build, compared with a decade or so for standard land-based nuclear plants. The Sudan Tribune has cited that country’s minister of water resources and electricity as saying the government in Khartoum has a deal to become the first foreign floating plant customer.

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

Our December Nuclear Digest, reported by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center, is out now. Here’s a quick taste of three nuclear issues arisin...

Bellona has launched the Oslofjord Kelp Park, a pilot kelp cultivation facility outside Slemmestad, about 30 kilometers southwest of Oslo, aimed at r...

Our November Nuclear Digest by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center is out now. Here’s a quick taste of just three nuclear issues arising in U...