Arctic Frontiers: Disinformation, Security and the Northern Sea Route

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

News

Publish date: April 10, 2014

Written by: Anna Kireeva

News

MURMANSK – The Northern Sea Route will not become an alternative to the Suez Canal, but nonetheless could be a viable maritime shipping route if cargo traffic, safe navigational seasons, and the shipping and icebreaker fleet are all magnified.

That’s a lot of ifs for a proposal that could significantly alter if not destroy the fragile arctic ecosystem, one of the most pristine and untouched left on earth.

But with multi-national oil majors and transport consortiums looking to cash in on shrinking ice volumes in Arctic Sea regions, climate change is poised to become a bankable asset.

That’s in any case what Russia’s Federal Administration of the Northern Sea Route seemed to be certain of when they met on Tuesday in Murmansk at a conference called “Arctic Logistics.”

Representatives at the conference said that one of the most important advances toward making the Northern Sea Route a sustainable passage from West to East was the establishment of criteria for allowing ships into its waters – criteria that have been spelled out in a piece of Moscow legislation called “On the Northern Sea Route.”

The law establishes equal access to the route for ships of all flags, while discarding stipulations about ice class ratings for those ships. Therefore, regardless of whether a ship is structurally rated for navigating icy waters or not, it is welcome to use the Northern Sea Route between the months of June and November.

That no ice ratings are required by the law seemed to pose no quandary for the route administration’s chief, Alexander Olshevsky, despite a prominent mishap last September , when the Nordvik cruiser, a ship with no ice class rating and a damaged hull, skittered and remained off course for several days.

The lack of rescue infrastructure along the Northern Sea Route left would-be rescuers scratching their heads about how to prevent the vessel from spilling tons of diesel fuel into Arctic waters. After two weeks adrift, the Nordvik was finally guided to port when two nuclear icebreakers taking part in a vanity parade of the Russian Navy’s flagship battle cruiser, the Peter the Great, across the Northern Sea Route were allowed to divert for the foundering vessel’s rescue.

In Olshevsky’s assessment at the conference, its safe enough to just require vessels of any class to enlist the services of an icebreaker – although in the Norvik’s case, navigation was allowed without icebreakers. Russia’s Seafarers Union castigated the decision-making process that allowed such frail vessel into Arctic waters.

“The [Nordvik] accident was a direct threat to the lives of sailors and the ecology of the Arctic” read the statement the union released at the time of the misadventure. “Vessels like that should not be sailing on [Northern Sea Route] because they are not capable of withstanding the ice conditions.”

But Olshevsky asserted to the conference that, “The new regulations have already stood for a year and establish conditions for which icebreaker escort is necessary.”

He instead focused on the amount of cargo that has been transported though the Northern Sea Route, saying in 2012 that 3,895,900 tons of cargo has passed through the Arctic corridor, and that in 2013, that figure rose slightly to 3,914,001 tons.

Olshevsky’s figures, however, are somewhat misleading, as they incorporate weights of cargos that not only passed the entire, though approximate, 5,600 kilometer length of the Northern Sea Route, but also those cargos that passed between ports within the route itself.

According to The Arctic Council, the volume of cargo passing along the entire route was a mere 1.26 million in 2012 with a 7.5 percent increase to 1.36 million in 2013.

Where he was correct was his assessment that the Northern Sea Route is hardly a competitive alternative to the Suez Canal, which in 2013, according to official figures presented at the Suez Canal Traffic Statics website, saw the passage of 753.4 million tons of cargo.

Olshevsky noted that in 2012, there was less ice present in the Arctic than at anytime in history since records began to be kept. In 2013, ice cover rose slightly.

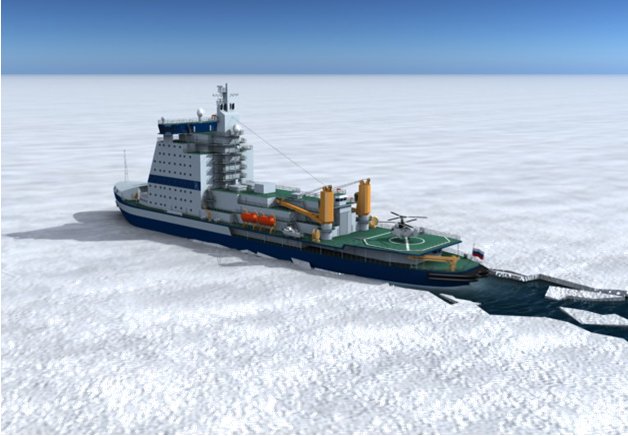

“However the situation turns out with climate chance, we nevertheless need new icebreakers to work the Northern Sea Route,” he said. “Even if the ice continues to melt, the [annual] navigational period will grow longer, the quantity of cargos will increase, and the regions for resource development will expand.”

Expanded shipping through the Northern Sea Route

It is entirely the discretion of the Russian Federal Administration of the Northern Sea Route as to who is permitted to pass through.

Permission is given on the foundation of a application filed ship owners, which, among other things, must contain confirmation that the ship owner has guaranteed a given ship conforms to the rules governing its passage through the Northwest Sea Passage.

Olshevsky said the Northern Sea Route Administration in 2013 received 718 permission applications and initially refused 83 vessels passage. When the majority of these vessels provided additional documentation, they were allowed to pass, and only 18 vessels – or 3.5 percent of total applicants – were denied passage.

It remained unclear whether the same application procedure and ice classification rules applies to ships simply navigating between ports within the Northern Sea Route, though the circumstances surrounding the near-sinking of the Nordvik would suggest they don’t.

A famous denial of permission

“All ships that were denied obeyed the decision of the administration, accept for one – the Arctic Sunrise – belonging to Greenpeace” said Olshevsky, in reference to the Greenpeace vessel that launched an offshore drilling protest at the Prirazlomnaya platform, an Arctic oil drilling platform owned by Russian state gas monopoly Gazprom. All 30 aboard the vessel, who represented 18 different countries, were arrested on piracy charges, later reduced to hooliganism.

They were held in Russian remand jails before President Vladimir Putin issued an amnesty in December in what many human rights activists dubbed a “cynical” and “cosmetic” effort to clean up Russia’s tarnished human rights record in the run-up to the Sochi Winter Olympics.

Olshevsky said the Arctic Sunrise “disobeyed he Northern Sea Route Administration, sailed into the Northern Sea Route, and as a result was ordered back, after which it continued toward the Prirazlomnaya Platform – all know how that ended.”

He added that the Arctic Sunrise had received four previous rejections to its applications to enter the Northern Sea Route, which Olshevsky said were a result of mistakes in the documents its crew submitted, its expired certification certificate, an incorrect specification of its class and other errors.

Ecological risks and whether or not the Arctic is ready

Aside from discussion the development of the Northern Sea Route, a large number of those in attendance wanted to focus on the ecological issues at stake in the development of these Arctic projects. The Arctic environment represent unique and pristine and therefore demand “cooperative measures for their protection,” said Murmansk Regional Lieutenant Governor Grirogy Straty.

Norway’s Consul General Øle Andreas Lindeman said that, despite the experience of specific countries and their aims to develop safe oil and gas extraction technology for drilling the Arctic, “the best decisions would not to pollute it.”

“We are now taking the accumulated experience in the oil and gas sector from land to sea, and in the event of any mistakes, we won’t get any second chances – the delicate nature of the Arctic won’t give us one,” said Lindeman.

Realistically looking at he situation he said that companies and operators who are working or plan to work in the Arctic region will hardly escape accidents in the northern seas, and therefore much will depend on international structures that are devoted to monitoring the situation.

Does the Northern Sea Route really cut shipping times?

Whether the Northern Sea Route offers any real slashes in cargo transport time and efficiency was a question left unaddressed by the conference, but was taken up in 2009 by the Danish Institute for International Studies in a report entitled “Are the Northern Sea Routes Really the Shortest?”

The report compares 14 of the world’s most heavily trafficked sea routes and compares their distances when routed through the Panama Canal, the Suez Canal, the Northwest Passage, the Northern Sea Route, and Suez Malaca.

In only 27 percent of the examined cases did the Northwest Sea Route present what the Danish institute identified as the “shortest route,” in comparison to the other three. In another 27 percent of the cases, it was actually identified as being a “marginally longer route.”

On 46 percent of these routes, the difference in distance as compared to the other three was statistically insignificant, and judged the routes, give or take a few dozen kilometers, to be a of nearly identical distances.

Charles Digges (charles@bellona.no) contributed to and translated this report.

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

Our December Nuclear Digest, reported by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center, is out now. Here’s a quick taste of three nuclear issues arisin...

Bellona has launched the Oslofjord Kelp Park, a pilot kelp cultivation facility outside Slemmestad, about 30 kilometers southwest of Oslo, aimed at r...

Our November Nuclear Digest by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center is out now. Here’s a quick taste of just three nuclear issues arising in U...