Not whether, but how fast on CO₂ storage in Norway

The following op-ed by Eivind Berstad, Bellona’s CCS team leader, originally appeared in Teknisk Ukbladet. When the European Free Trade Associatio...

News

Publish date: August 25, 2003

Written by: Rashid Alimov

News

According to information obtained from open sources by the Environmental Rights Centre Bellona, or ERC Bellona, the St. Petersburg representative office of the Bellona Foundation, at least 15 then-Soviet submarines suffered nuclear reactor accidents at an average of more than one accident every two years.

The history of Bellonas inquiry to the Defence Ministry to declassify this information began last year on July 18th, when ERC Bellona sent a written appeal to Russias defence minister, Sergei Ivanov, requesting he make public information about accidents that occurred aboard Soviet nuclear submarines.

The letter to Ivanov read, in part, that according to information that ERC Bellona obtained from various open sources, the nuclear reactors of the nuclear submarines tactically numbered K-19, K-387, TK-208, K-279, K-447, K-508, K-209, K-210, K-216, K-316, K-462, K-38, K-37, K-371, and K-367, suffered at various times accidents and technical failures. It is known that as a result of these accidents, people suffered and radioactive emissions in the environment were registered. Despite this, the full results of these emergencies remain to this time concealed from the public.

These subs, which are laid up at the bases of the Russian Northern Fleet, have been retired and await full dismantlementsome with their spent nuclear fuel still on board. Others, like the infamous K-19, have been defuelled and are slated for destruction. Still others have been fully destroyed, mostly with US threat reduction funding, and their spent nuclear fuel sent to the Mayak Chemical Combine for reprocessing.

Famed environmentalist and ERC Bellona chairman, Alexander Nikitin, said in a recent interview that we have asked Ivanov to declassify the data about the radiation accidents in strict accordance with Russian legislation.

Nikitin himself is no stranger to Russias cult of secrecy: In 1995, he was accused of treason through disclosing state secrets while writing Bellonas well-known report entitled The Northern Fleet: Potential Sources of Radioactive Contamination of the Region. After his arrest, 11 months in custody of the secret police, and a 5-year legal struggleduring which it was proven in court that all information Nikitin had compiled for the report came from open sourceshe was fully acquitted of the charges by Russias Supreme Court in January 2000.

Response to Ministry Letter ArrivesWith a Surprising Signature

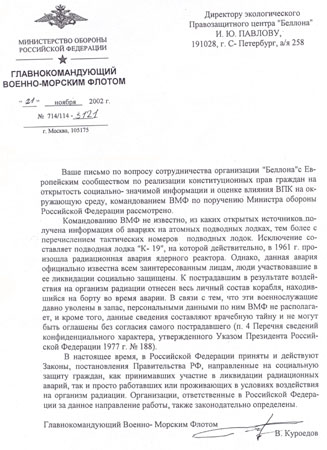

In November 2002, ERC Bellona received an official response to its inquiry on declassifying the submarine accidentsbut it did not come from Defence Minister Ivanov, to whom it was addressed. Instead, it came from none other than the Russian Navys commander-in-chief Vladimir Kuroyedov.

The Navy is unaware of any open sources from which the information about accidents aboard nuclear submarines has been obtained, especially information enumerating the tactical numbers of the submarines, Kuroyevov wrote.

It seems that neither the navys commander-in-chief nor his assistants read open literature, including environmental literature, said Pasko in an interview. Anyway, denying all those accidents, and denying societys right to know about those accidents, is simply absurd.

Pasko, like Nikitin, was arrested on treason charges in Vladivostok on November 20th 1997. The FSB accused Pasko of espionage based on his collaborative work with Japanese journalists, which included giving Japanese television a videotape made in 1993 that showed the Russian Pacific Fleet ships illegally dumping nuclear waste in the Sea of Japan.

In 1999, the court acquitted Pasko of treason, but convicted him of abuse of his official authority for his supposedly negligent contacts with the Japanese media. Pasko was immediately amnestied, but he appealed the amnestyand, by default, the convictionto the Supreme Court on the foundation that an innocent man cannot be amnestied.

The unexpected result of that appeal was new trial and a conviction in December 2001 on the same charges of treason that Pasko had earlier been acquitted for. The foundation of that conviction was a set of notes he made while attending a meeting of naval brass while working as a reporter for the Pacific Fleet newspaper, Boyevaya Vakhta. In December 2001, the Pacific Fleet Court in Vladivostok acquitted Pasko of charges that he had passed the noteswhich allegedly concerned "secret naval manoeuvres"to the Japanese media, but convicted him for allegedly intending to pass the notes on.

His attorneys, Bellona and rights groups throughout the world maintained that these charges were fabricated by the FSB and relied heavily on two now-defunct secret Defence Ministry decreesNos. 010 and 055.

Pasko was sentenced to four years hard labour in a prison colony near the Russian Far East town of Ussuriysk. He was, however, paroled for good behaviour on January 23rd 2003 by the Ussuriysk City Court after serving two-thirds of his sentence. Pasko has never accepted any blame for the charges that sent him to prison. He is working with his lawyer, ERC Bellona Director Ivan Pavlov, to clear his name of the unlawful conviction.

But it will be a long road. Having exhausted all his means of reversing the 2001 conviction in Russia, Pasko and his legal team have sent his case to the Strasbourg Human Rights Court.

K-19: The Widowmaker

Kuroyedov, in his terse reply to ERC Bellona, admitted to only one accident: the one that took place in 1961 aboard the Northern Fleets K-19, whichas the subject of a recently released, star-studded, and highly fictionalised Hollywood film K-19: The Widowmakeris hard to keep under wraps. The ballistic missile Hotel class K-19s near-catastrophe was the first nuclear accident to occur aboard a Soviet nuclear submarine.

On July 4th 1961, during exercises in the North Atlantic, close to NATO facilities, a leak developed in the K-19s reactor cooling system. The leak caused a sudden drop in pressure, setting off the reactor emergency systems. Left unchecked, the leak could have led to a core meltdown of the reactor.

To prevent the overheating of a reactor, superfluous heat has to be removed, and this is done by continually circulating coolant through the reactor. There was no built-in emergency system for supplying coolant to the K-19s primary reactor circuit, and it was feared that an uncontrolled chain reactionleading to a nuclear explosion several times more powerful than Hiroshimamight start.

In the tension of the Cold War, the K-19s crewclose as it was to NATO installationscould neither call for nor accept American help. Likewise, a reactor explosion, had it occurred here, in the proximity of the NATO facilities, might have been construed by the United States as a nuclear first strike by the Russians.

Aboard the K-19, an improvised system to supply coolant to the reactor was devised. This required officers and midshipmen to work under conditions of extreme radioactivity in the more remote areas of the reactor compartment as they tried to repair the leak in the primary circuit.

Radiation exposure on the K-19 came primarily from contaminated gases and steam. All of the crew was exposed to substantial doses of radiation, and eight men died of acute radiation sickness after having undergone doses of 50 to 60 sieverts. The crew was evacuated to a Soviet diesel submarine, and the K-19 was towed home to the Kola Peninsula, repaired, and continued to serve for several more years.

The film version of the incident aboard the K-19starring Harrison Ford and Liam Neesonwas produced by Katherine Bigelow, who called the film a fascinating tale of ordinary people who became heroes when faced with a tragic situation. According to survivors of the K-19 incidentmany of whom are members of St. Petersburgs Submariners Club and were presented with the movies original scriptthe films accuracy stops with its treatment of the reactor failure. Otherwise, the script generated anger and many among ex-K-19 sailors threatened lawsuits against Bigelows studio for the films portrayals of drunken and incompetent crew members, according to Moscows English-language daily, The Moscow Times.

Other detailed, but unofficial information about the accident can be found in Bellonas 1996 report The Northern Fleet at www.bellona.org.

Kuroyedov Still Evasive

Despite the accrual of informationboth fact and fiction, official and unofficialabout the narrowly averted K-19 disaster, Kuroyedovs acknowledgement of the K-19 incident contained no elaboration. Of the list of submarines suffering reactor accidents submitted by ERC Bellona, Kuroyedov wrote that the exception is the K-19 which did in fact, in 1961, experience a nuclear reactor accident.

But this accident is officially known to all concerned parties, and people who participated in the accidents cleanup are receiving social benefits, continued Kuroyedov in his letter. The entire crew of the ship, which was onboard during this accident, have been counted as victims. As those servicemen were transferred to the naval reserves, the navy possesses no personal information concerning them, and furthermore, this information is subject to doctor-patient confidentiality and cannot be released without the consent of the patient.

Kuroyedov neglected to mention the K-19s death toll: lieutenant commander Povstyev, lieutenant Korchilov, sergeants Ryzhikov, Ordochkin and Kashenkov, seamen Penkov, Savkin and Kharitonov. The information on their deaths was finally published by retired rear admiral Nikolai Mormul, a harsh critic of Soviet secrecy and official fabrications about Russias nuclear industry. In the early 1990s, Mormul was among the first to draw attention to the necessity of dismantling laid-up submarines and handling their nuclear waste. Mormul, with Nikitin, was one of the authors of Bellonas controversy-inspiring North Fleet report.

Kuroyedov added in his letter that currently, Russia has adopted and enacted legislation for the social protection of citizens who have taken part in the cleanup of consequences of nuclear accidents as well as those working or living in conditions that would expose them to radiation.

Organisations responsible for this kind of work have been appointed and legislatively codified," concluded Kuroyedov.

Pasko Takes Issue with Kuroyedovs Letter

Pasko, who has interviewed several survivors of various radiation accidents on Soviet and Russian submarines, did not buy the naval commanders response.

The naval commanders concern about the doctor-patient confidentiality seems to be touching, Pasko said wryly. First, all of them had to sign a statement not to disclose information about the accident. Then, they only learned about their right to compensation or special social privileges dozens of years later. And because of the secrecy surrounding their conditions, civilian doctors could only wonder about the causes of their poor health.

Even the social security for the K-19 victims alluded to by Kuroyedov, Pasko said, was grossly inadequate.

The social security mentioned by Kuroyedov is first of all, financially inadequate, and, secondly, accessible only for those who are registered in the decrees for social relief, Pasko said. However, it was accepted practice that mostly officers were registered in the documents, and seamen and sergeants were not. Who can say where they live, or whether they are alive at all? I doubt Kuroyedov is interested in answering those questions. As he says: those servicemen were transferred to the reserves, the navy has no personal information.

Kuryedov to Court

Due to what ERC Bellona says is an unsatisfactory response from Kuroyedov, it appealed to the Moscow Presnya District Court with a complaint that the Defence Ministry had violated the Russian constitution. ERC Bellona also said the Defence Ministry had violated a host of statutes from a host of laws in particular, the law On State Secrets.

But the Presnya District Court refused to consider the case and formulated a rejection that said that cases concerning state secrets must be considered at the Moscow City Court.

ERC Bellonas Pavlovwho is responsible for writing the legal complaints in these proceedingsclaimed that the case cannot be related to the state secrecy law until the defendant, in this case the Defence Ministry, can prove that it is.

The Moscow City Court, during of one its sessions on August 12th 2003which coincided with the third anniversary of the Kursk submarine disasteragreed that the case fell outside the jurisdiction of the Presnya District Court. The city court will be considering the case this autumn.

Defence Ministry representatives were not available for comment on the case. It is ERC Bellonas assertion that, because the Defence Ministry is concealing significant information and disregarding official inquiriesthe inquiry about the submarine accidents being a case in pointit will have a difficult time constructing its defence.

Legislation

According to Russian legislation, state information resources are open and available for all. The only exception is information that the law defines as restricted as described under Article 10 of the law On Information, Information Technologies and Protection of Information.

Information about emergency situations, ecological information and other information pertaining to the safety of populated areas, industrial infrastructure, and civil population cannot be ascribed to the category of restricted access.

Also available to the public and forbidden from classificationaccording to Clause 7 of the law On State Secretsis any information pertaining to civil emergencies and catastrophes that threaten the safety and health of the population; to natural disasters and official forecasts about disasters and their prospective consequences, as well as information about ecological conditions.

On the basis of this, and Article 15 of the law On State Secrets, ERC Bellona asserts that information about accidents and incidents on the nuclear submarines cannot be classified or restricted in any way, as reactor and other radiological accidents aboard submarines have a direct impact on the environment.

Augusts Accidents

Pasko, who has conducted extensive investigations of nuclear safety in the Russian Far East, said: Its symbolic that we are filing this complaint to the Moscow City Court in August, a month when we cannot but recall the Chazhma and the Kursk accidents.

The Chazhma Bay accident occurred on August 10th 1985 when the two-reactor Echo class submarine K-431, project 675, was being refuelled near Vladivostok. During the refuelling, a thermal explosion ruptured both the aft bulkhead of the submarine and its pressure hull, hurling the freshly fuelled nuclear reactor core, as well as the roof of the refuelling hut, some 80 metres around the refuelling site. A resulting fire in the reactor compartment was localised after four hours.

The radioactivity released during the explosion was around one seventh of the total released in the Chernobyl disasteror seven times that which was released during the Hiroshima bombing.

According to the official casualty figures, 10 were killed instantly, 10 suffered acute radiation sickness and 39 were irradiated at sub-acute levels. The ship itself has not been decommissioned yet and still poses a danger, floating near its berth, its bow beached on the shore. The spy scandal surrounding Pasko temporarily postponed last spring Japanese financial aid for decommissioning a number of the Pacific Fleets ailing submarines, including the K-431. As of last fall, the Japanese aid project has been renewed.

The nuclear submarine Kursk of the Oscar-II classthe largest attack submarine ever builtsank on August 12th 2000 in the Barents Sea during a Northern Fleet military exercise. The Kursk, which went down when torpedo fuel exploded in its torpedo bay, became the fourth nuclear-powered submarine from the Northern Fleet to sink.

All 118 people onboard died after international offers of help, which may have saved at least some of the crew, had been rejected by the Kremlin. After a week of Russian efforts, a Norwegian diving crew was finally permitted to open an escape hatch on the submarine, which it did in less than an hourbut by then the Kursks crew had been long dead, some from the initial blast, others from resulting fires, and the last survivors from oxygen deprivation.

The Kursk was partially lifted from the floor of the Barents Sea. But according to Bellonas data, the other nuclear submarines that the Russian navy has lost over the years are lying at the bottom of the ocean.

The K-8, a November class submarine, sank in the Bay of Biscay on April 8th 1970. The two-reactor submarine sank with 52 crew members onboard after a fire started in its central and rear compartments.

Another submarine, a Yankee class vessel with the tactical designation K-219, is lying at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean north of Bermuda. It sank on October 6th 1986 after an explosion in one of its missile tubes.

At the time of the explosion, only one of the submarines two reactors was running. One sailor died while trying to lower control rods into one of the reactors. Three others died in the smoke and fire that resulted from the explosion. The entire submarine sank, bringing with it its two reactors and 16 missiles with nuclear warheads.

A fire was also the cause of the Komsomolets disaster on April 7th 1989. The K-278, as the Komsomolets was designated, is lying in the Norwegian Sea at a depth of 1,685 metres with its reactor and two nuclear plutonium-based warheads on torpedoes. The fire, which occurred in the seventh compartments electrical system, caused short circuits throughout the K-278s electrical infrastructure that set off the single reactors emergency system. The disaster killed 41 sailors in icy arctic waters as the Komsomolets sank.

Currently, there are fears that both the Komsomolets reactor and warheads are leaking presenting a potential ecological danger to the Norwegian coast.

US Sub Accident Information Widely Available

In addition to Russian submarines, two American submarines are lying on the sea bottom. One is USS Thresherdesignated in US military terminology as the SSN-593which sank some 350 kilometres east of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, on April 10th 1963 during deep-diving tests. It took the lives of 129 officers, crewmen and civilian technicians. The ships remains were located on the sea floor some 2800 metres below the surface.

Another US submarine, the USS Scorpion, or SSN-589, was lost with its entire crew some 640 kilometres southwest of the Azores in May 1968. In late October 1968, the Scorpions remains were found on the sea floor over 3,300 metres below the surface. Its hull had suffered fatal damage, the cause of which is still unknown.

Information about both US submarine disasters, as well as information about other incidents within the US nuclear fleet during the Cold War, can be found at the official website of the US Department of Defence at www.defenselink.mil.

| Submarine accidents in the Northern Fleet | ||||||

| K-no. (fabric no.) class (Project) |

-Shipyard -Laid down -Launched |

Active service -Start date -End date |

Accidents | Present condition (Kola Peninsula) | ||

| K-19 (KS-19) (N901) Hotel (658) |

Sevmash

17/101958 11/101959 |

12/111960

July 1990 |

03/07 1961: Nuclear accident. Break down of the primary circuit, radioactivity discharge. 8 people died

15/11 1969: Collision with American nuclear submarine, the Barents Sea 24/02 1972: Fire, 28 people died 15/11 1978: Fire 17/08 1982: Fire |

Defuelled at Polyarny shipyard. The submarine is currently in a dry dock at Nerpa shipyard waiting for dismantlement. Discussions are underway on whether to convert K-19 into a museum. | ||

| K-387 (N801) Victor-II (671RT) |

KrasnoeSormovo shipyard 02/041971 02/091972 |

30/121972

1995 |

1967: Main condenser breakage (2 persons injured to death) | Laid-up in Gremikha;

Reactors not defuelled. |

||

| TK-208 Dmitry Donskoy Typhoon (941) |

Sevmash

30/06 1976 23/09 1979 |

12/121981

in service |

1986/87 Cleaning unit leakage | The submarine has been under upgrade and repairs at Sevmash shipyard since 1990, was to enter active service in 2003. | ||

| K-279 (N310) Delta-I (667B) |

Sevmash

1971 1972 |

22/121972

1993 |

1984: Collision with iceberg

1984: Leaky steam generator Dec. 1986: Fire |

Dismantled at Zvezdochka shipyard in Severodvinsk in 1998. Reactor section towed to Sayda Bay. | ||

| K-447 (N311) Delta-I (667B) |

Sevmash | 1973

~1998 |

1985: Leaky steam generator | The submarine was in service in 1997. Discussions are being held with CTR to fund dismantlement. | ||

| K-508 (N905) Charlie-II (670M) |

Krasnoe Sormovo

10/12 1977 03/10 1979 |

30/121979

1995 |

4/08 1995: Collision with surface vessel

Apr. 1984: Fire 1984: Leaky steam generator |

Laid-up in Ara Bay, Vidyaevo;

Last refuelling in 1990-91. |

||

| K-210 (N401) Yankee (667A) |

Sevmash | 06/081969

1980s |

1984: Leaky steam generator | Dismantled at Zvezdochka shipyard in Severodnisk. Reactor section towed to Sayda Bay in 1995-96. | ||

| K-216 (N424) Yankee (667A) |

Sevmash | 27/121968

1980s |

1984: Leaky steam generator | Dismantled at Zvezdochka shipyard in Severodnisk. Reactor section (8-compartment block) towed to Sayda Bay in 1994. | ||

| K-316 (N905) Alfa (705) |

Admiralty shipyard

26/04 1969 25/07 1974 |

Sep1978

~1994 |

1987: Reactor malfunction | Decommissioned at Sevmash shipyard in Severodvinsk in 1995;

Reactor section towed to Sayda Bay for storage. |

||

| K-462 (N01613) Victor-I (671) |

Admiralty Shipyard

03/071972 01/091973 |

30/121973

1996 |

1984: Critical underspace leakage of primary circuit

1986: Critical underspace leakage of primary circuit |

No data. | ||

| K-38 (N600) Victor-I (671) |

Admiralty Shipyard

12/041963 28/071966 |

05/111967

1991 |

1984: Critical underspace leakage of primary circuit

Mar 1985: Fire 1986: Critical underspace leakage of primary circuit |

Laid-up in Gremikha;

Reactors not defuelled; Main ballast tanks no. 1, 5, 6, 9, 11, 12, 13 are leaky. |

||

| K-371 (N802) Victor-II (671RT) |

KrasnoeSormovo shipyard 12/051973 30/071974 |

29/121974

~1995 |

1986: Critical underspace leakage of primary circuit | Reactors defuelled by Imandra service ship in autumn 2000.

Submarine laid up at Shkval shipyard in Polyarny. |

||

| K-367 (N609) Victor-I (671) |

Admiralty Shipyard

14/041970 02/071971 |

05/121971

1995 |

1985: Reactor control rod malfunction | Laid-up in Gremikha;

Reactors not defuelled. |

||

The following op-ed by Eivind Berstad, Bellona’s CCS team leader, originally appeared in Teknisk Ukbladet. When the European Free Trade Associatio...

For the past eight years, disinformation has dominated news around elections all over the world. Despite this, it is still a widely misunderstood con...

A ruling by the European Free Trade Association Court that Norway’s continental shelf falls under the European Economic Area Agreement could dramatic...

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway