New Managing Director for Bellona Norway

The Board of the Bellona Foundation has appointed former Minister of Climate and the Environment Sveinung Rotevatn as Managing Director of Bellona No...

News

Publish date: October 14, 2003

Written by: Charles Digges

News

The German-Russian deal, equal to $354m, is aimed at cleaning up the ever more crowded and contaminated Sayda Bay and providing, over the course of the next six years, an temporary onshore reactor compartment storage facility that will safely hold its current 50 radioactive reactor compartments—plus approximately 30 more compartments that the German and Russian governments expect will be shipped to Sayda within the next ten years as the Northern Fleet retires more submarines.

The deal was signed late last week by Russias deputy minister for atomic energy, Sergei Antipov, and Alfred Tacke, Germanys undersecretary of state for the Ministry of Economics and Labour, at the sidelines of a summit between Russian President Vladimir Putin and German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder held in the Siberian city of Yekaterinburg.

With the submarine project we make an important contribution in the fight against the spread of nuclear weapons-usable materials, Tacke said after the signing. At the same time, we give a strong impulse for German-Russian co-operation.

The €300m expenditure is seen by Germany as part of its obligation to the framework of the 10 plus 10 over 10 plan agreed upon by the Group of Eight industrialised nations, or G-8, in 2002 at the groups summit in Kananaskis, Canada.

Under this agreement, seven of the G-8 member countries will contribute $10 billion toward solving nuclear dismantlement and security issues in Russia. The United States, also a G-8 member, will contribute another $10 billion toward the pledge, for a total of $20 billion in nuclear dismantlement funding for Russia over the next 10 years. The countries now have nine years to make good on their word.

A representative of the German Economics and Labour Ministry, who was interviewed by email by Bellona Web, confirmed that the €300m is just a start to what he said would be an overall €1.5 billion contribution within the 10 plus 10 over 10 framework. He added, though, that getting the current deal onto the table in a form that both sides could accept was no easy task. He refused to elaborate. He did say that the remaining €1.2 billion commitment would help finance other radioactive waste storage projects as well, though the government had not yet decided what its next project will be.

What Germany Will Build At Sayda Bay

Through its most prominent nuclear decommissioning contractor, Energiewerke Nord GmbH, or EWN, Germany will build an enormous 5.6 hectare warehouse type enclosure on the banks of Sayda Bay for onshore storage of the irradiated reactor compartments and hulls currently stored afloat in the bay. The Germans will also improve transportation and mechanical infrastructure for dealing with the reactor compartments.

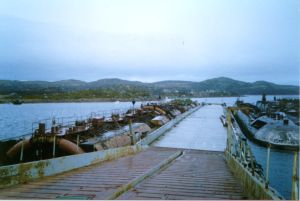

Sayda Bay, originally a fishing village just inside the Murmansk Fjord north of the Nerpa shipyard, was commandeered by the Russian Navy in 1990 as a storage site for irradiated submarine hulls and reactor compartments that the fleet cuts out of its retired subs. At the time, the Russian Navy estimated it could store its reactor compartments on the water at Sayda Bay for 10 years, during which, it was hoped, a more permanent solution would be found.

By 1995, some 12 reactor compartments—unloaded of their spent fuel but still highly irradiated —were tied to Saida Bays piers. By 2003, as the Russian Navy dismantled more submarines, the figure had increased to some 50 reactor compartments. Some of these—although in a recent interview, Minatom would not say how many—still retain spent nuclear fuel inside their reactors.

Dieter Rittscher, head of EWN, said in a recent interview with Russian media that the piers—some of them so dilapidated that they could crash down and sink the irradiated hulls—were obviously packed beyond their capacity.

The new project, developed jointly by EWN and Moscows nuclear research Kurchatov Institute, envisions safe storage for irradiated reactor compartments that have had their fuel removed for as long as 70 years—the amount of time it will take the irradiated steel and titanium hulls to reach manageable levels of radioactivity. This interim storage facility is one of the types of temporary radioactive waste facilities for which Bellona has long lobbied.

The rapid construction of the storage facility is crucial because it has strategic significance, said Rittscher. Without a 5.6-hectare warehouse, Rittscher noted, dismantlement and storage of further submarines at the Kola Peninsulas shipyards would be impossible.

Along with the construction of the warehouse itself, EWN will oversee the installation of some 70 special transport devices for the irradiated hulls and reactor compartments to move them to their new onshore berths.

EWN, as per the agreement it signed with Russia, will maintain total control of which contractors are chosen to carry out the construction of the facility. According to Rittscher, the Russians will carry out construction—60 percent of the projects work. The other 40 percent of labour toward the projects completion—as design, research, tooling of heavy machine components and other work not taking place in Russia—will be handled in Germany by German firms.

Flagging G-8 and Russian Environmental Efforts Given a Nudge

The G-8 project, over the last year, looked to be in danger of foundering until this years G-8 summit in Evian, France, after which the Group of Eight and other European countries opened their coffers and began dismantling submarines and devising nuclear cleanup projects at a furious pace. Germany was the most recent to join the bandwagon.

The first country to commit itself to a major project was, in fact, Norway, a non-G-8 nation, which put up €10m to destroy two Russian Victor II class submarines. This process has already begun at the Nerpa and Severodvinsk shipyards in Northwest Russia. Next, Japan began a so-called pilot project to dismantle a derelict Victor III class submarine from Russias Pacific Fleet, staking how it would spend another $160m in nuclear dismantlement funding it has earmarked for Russia on the outcome of the project. The United Kingdom followed shortly thereafter by pledging to dismantle two Oscar I class subs.

The Evian summit also spurred an outpouring of financial donations to the Northern Dimension Environmental Partnership, or NDEP, an environmental assistance fund held by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, or EBRD. This funds coming into force had depended on the signing of the Multilateral Nuclear Environmental Programme in the Russian Federation, or MNEPR, which was inked in Stockholm in May.

Funding from the United Kingdom, France, and Canada more than doubled NDEPs account for nuclear cleanup in the Russian Northwest, giving it a total of €142m for such projects. A meeting of NDEPs contributor countries, which will include its original donor nations of Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden, is expected to take place in late October or early November, according to EBRD officials. This gathering of the donor nations is meant to set funding priorities for nuclear cleanup projects in Northwest Russia.

Pitfalls

The German project seems, by all accounts, to be a micromanaged venture overseen by one of Europes most respected nuclear decommissioning firms. But as the recent sinking of the November class K-159 shows, donor nations cannot be too careful or too thorough in reviewing each stage of the nuclear remediation projects they are funding.

The K-159 sank in 240 meters of water with 800 kilograms of spent nuclear fuel while being towed from the Gremikha Naval Base on the Kola Peninsula to the Polyarny shipyard near Murmansk for decommissioning. Nine of the 10 crew members aboard were drowned. The towing of rusted-out, leaky, derelict submarines is an extremely dangerous practice that the Bellona Foundation has many times tried to persuade the Russian government to quit, urging safer methods.

The K-159 incident was not financed by a donor state. But when it was revealed that the two submarines that Norway is dismantling were transported to their respective decommissioning points in the same manner, it caused a minor political scandal between the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which had signed the deal with the Russians, and Norways Parliament, which had strongly recommended more thorough safety and feasibility studies for submarine dismantlement projects involving Norway.

The representative of the German Economics and Labour Ministry told Bellona Web that the K-159 case, and subsequent Norwegian scandal, underscored to EWN and the German government the importance of overseeing every step of its Sayda Bay project.

The Board of the Bellona Foundation has appointed former Minister of Climate and the Environment Sveinung Rotevatn as Managing Director of Bellona No...

Økokrim, Norway’s authority for investigating and prosecuting economic and environmental crime, has imposed a record fine on Equinor following a comp...

Our op-ed originally appeared in The Moscow Times. For more than three decades, Russia has been burdened with the remains of the Soviet ...

The United Nation’s COP30 global climate negotiations in Belém, Brazil ended this weekend with a watered-down resolution that failed to halt deforest...