New Managing Director for Bellona Norway

The Board of the Bellona Foundation has appointed former Minister of Climate and the Environment Sveinung Rotevatn as Managing Director of Bellona No...

News

Publish date: July 16, 2003

Written by: Charles Digges

News

The apparent outbreak of international non-proliferation and environmental philanthropy is comprised of five countries that over the past month have donated more than $130m toward Russias efforts to decommission the countrys retired and rotting non-strategic submarines, as well as for nuclear cleanup in some of Northwest Russias most contaminated areas. These nations also want to develop safer methods of storing spent nuclear fuel, or SNF, in both Northwest and Far East Russia, where Russias nuclear submarine bases are located.

Nuclear experts say the upsurge of funding is due to some hard non-proliferation politicking at Junes Group of Eight, or G-8, summit in Evian, France, where France, the current G-8 president, and the United States lobbied fellow G-8 members to make good on their $20-billion pledge made at last years Kananaskis summit. Under this plan—known variously as the 10 plus 10 over 10 or Global Partnership programme—the $10 billion would be raised over the next ten years by seven of the G-8s nations, and the United States would contribute a matching contribution of $10 billion.

John Wolfsthal, deputy director of the Non-Proliferation Project at the Washington-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said in a telephone interview that the nearly simultaneous funding from Norway, Britain, Japan, Canada and France was the consequence of agreements reached at the Evian summit.

Its the result of the Evian G-8 summit, said Wolfsthal, who was also a senior non-proliferation expert with the US Department of Energy, or DOE, during the Clinton administration. France put forth a lot of effort, as did the United States, which is sort of the main driver of the 10 plus 10 over 10 plan, so what we are seeing now are the residuals of that.

Much of the current cash releases were facilitated by the signing of the Multilateral Nuclear Environmental Programme in the Russian Federation, or MNEPR, in May, which made possible the release of some €62m for nuclear cleanup in Russia from the Northern Dimension Environmental Partnership, or NDEP. The NDEP fund is held by the London-based European Bank of Reconstruction and Development, or EBRD. Due to the current spirit of G-8-driven donations, NDEP fund will climb by nearly €80m for a total of €142m earmarked specifically for nuclear cleanup projects in Russias Northeast.

All of this funding flows into one multilateral fund for nuclear cleanup in the Barents Sea area and in the East Coast of Russia, Vince Novak, head of EBRDs nuclear safety division, told Bellona Web in a telephone interview from London. Your organisation Bellona has done excellent in this area.

Novak continued to say that NDEP and EBRD—thanks in part to Bellona Web publications—have open and transparent cooperation with our colleagues at Minatom, as the Russian Ministry of Atomic Energy is called.

They fully agree that we need a master plan for dealing with spent nuclear fuel and for creating a basis for favourable programmes, Novak said. The whole point is to solve the problem as soon as possible.

Novak said he expected a meeting of NDEPs contributing nations to take place in late September or October, after which those projects that are not already underway will begin. Aside from NDEPs original contributors—Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden—France, the United Kingdom and Canada will also be present at the contributors meeting.

We also expect other countries to join NDEP by then, Novak said.

What This Funding Will Cover

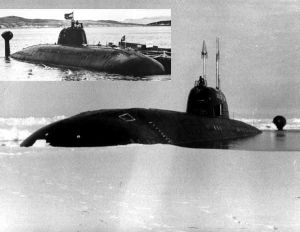

Of the 191 laid-up nuclear submarines in Russia, 115 are located at the Northern Fleet bases. Of those, around 70 still have spent fuel on board, and approximately only 40 have been fully dismantled. SNF from more than 100 reactors is in storage at onshore bases and nuclear service ships, with some 130 reactor cores still on board retired submarines.

Norway—the first country to get the dismantlement projects off the ground—signed off on a €10m project on June 27th to dismantle two Victor III class submarines from the Northern Fleet. On June 30th, Britain pledged $56m and France pledged $40m to help Russia scrap retired submarines that sit rusting afloat, Russias Deputy Minister of Atomic Energy Sergei Antipov told reporters this week.

Subsequently, on June 29th, Japan inked an additional and long-promised deal with Russia to dismantle one Victor III class submarine in what one Tokyo official estimated to be a $5m to $8m pilot project to gauge costs of dismantling more of the remaining 40 non-strategic submarines the Russian Pacific Fleet has retired. Of those 40 barely floating vessels, 36 still have spent nuclear fuel in their reactors, posing a high risk of radioactive contamination.

And on July 15th, Novak said, Canada announced it would contribute another $21.3m to the NDEP fund.

The combined contributions of Norway, the UK and Japan alone will result in the dismantlement of at least five non-strategic submarines that could not be covered by the US Cooperative Threat Reduction, or CTR, programme of 1992, which is congressionally limited to destroying only ballistic missile submarines that once targeted the US. This funding will also help tackle the 248 reactor cores that are stored at Northern Fleet bases and which are equivalent to 99 tonnes of uranium in SNF.

What Norway Will Do

Norway, a non-G-8 country, was the first to sign a post-Kananaskis non-strategic sub dismantlement contract with the Russians. But it was a shaky start. The contract to destroy two Victor III class attack submarines was initially scheduled for signing between Russias Antipov and Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs Kim Traavik on June 12th.

But the Norwegians balked at the signing once they discovered that Minatom expected Norway to pay for reprocessing the submarines spent nuclear fuel. A 2002 policy adopted by the Norwegian Parliament—of which Antipov would have been expected to know—forbids that nuclear dismantlement funding from Norway pay for any reprocessing activities. The contract was sent back to Moscow for rewrites.

Antipov was cited by the Minatom-sponsored website Nuclear.ru as being taken by surprise when presented—on the very day the contract was to be signed—with Norways negative position on the SNF reprocessing issue.

Antipov said that the contract—which had been in preparation since the beginning of this year—had come at Norways initiative. After the events of June 12th, Antipov said, both sides had reached a mutual understanding and signed the document. According to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Russian side accepted that none of Oslos funds would go toward reprocessing.

In Norways view, the Russians are responsible for dealing with the spent uranium fuel, said Traavik in a statement released to Bellona Web. There is no question of our paying to reprocess it.

He added that he was very pleased that the final pieces needed to achieve an agreement have now fallen into place. There is an urgent need to begin dismantling these submarines—many of them are in a grave state of disrepair.

He said that the dismantlement work began as soon as the contracts were signed and that the two Victor III class subs will be destroyed within the year.

The new contract, much as the old one, stipulates that Norway will transfer the €10m to the Nerpa shipyard in the Murmansk region and to the Zvyozdochka shipyard in Severodvinsk in the Arkhangelsk region, both in Russias Northwest, said Kare Eltervag, a spokesman for the Norwegian Foreign Ministry in a telephone interview.

But unlike the old agreement, the new one will only cover removing the spent nuclear fuel, dismantling the subs and shipping the fuel to a point of safe storage, both Norway and Minatom confirmed. At the same time, Norway will also increase its support for cleaning up two Russian naval bases—one at Andreyeva Bay, in the western part of the Kola Peninsula, and Gremikha, on the peninsulas eastern edge.

Eltervag could not elaborate on how Norway and Russia had managed to circumnavigate the reprocessing issue—something even US government submarine dismantlement contracts have failed to do—and Norwegian Foreign Ministry officials responsible for negotiating the new contract were on vacation and unavailable for comment.

What remains in question, then, is where the fuel will be stored and whether the Russians will reprocess it—a question that will be decided by Minatom, none of whose responsible officials were available for comment this week. The fuels most likely destination is, at least temporarily, a storage facility at the Mayak Chemical Combine, which reprocesses—among other types of fuel—spent submarine fuel, and is the most radioactively contaminated place on earth.

Reprocessing spent nuclear fuel leads to the creation of more reactor-grade plutonium, which can be enriched to weapons-grade plutonium and used in nuclear bombs. Reprocessing is effectively a criminal act, said Vladimir Kuznetsov, an ex-nuclear regulator in Russia who now heads up the nuclear and radiation safety division of Russias Green Cross environmental organisation. All the spent nuclear fuel must be buried in proper storage facilities that must be located near where the subs are located now.

Japans Pilot Project on Sub Dismantlement

According to the highly placed government official in Tokyo, Japan will not be paying for reprocessing the fuel it extracts from the Victor III class submarine it will be destroying as part of its pilot project.

Norway does not reprocess nuclear fuel from its two small research reactors—one of which is used for medicinal study—electing instead to bury its SNF in adherence to the open fuel cycle philosophy, which prohibits the recycling of radioactive waste for plutonium. Japan, on the other hand, supports the closed fuel cycle. But in the case of its dismantlement project in Russia, Japan said it will depart from its reprocessing policy.

We will not be paying for the reprocessing of any spent nuclear fuel in this project, said the Japanese government official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

The official said the contract for dismantling the sub is expected to be fulfilled within 18 months. A spokesman for Minatom confirmed this.

Japanese Foreign Minister Yoriko Kawaguchi visited the Russian Far East on June 28th and 29th for the ceremonial signing of the contract for the project, which is dubbed Star of Hope.

Russian submarines taken out of service in the Sea of Japan, where the Pacific Fleet is located, represent a risk of environmental contamination and a security threat, Kawaguchi said, according to Agence France Presse. That is why this project to dismantle the submarines must be carried out conscientiously.

According to the high-ranking Japanese official, the pilot project has been estimated to cost between $5m and $8m. But although he said the government has a more concrete figure in its budget for the project, he would not be more specific.

Japan has been deeply involved in Russian nuclear cleanup and disarmament projects. In 1993 Japan established the joint Japan-Russia Committee on Cooperation to Assist the Destruction of Nuclear Weapons Reduced in the Russian Federation, and pledged $200m to help Russia decontaminate its Soviet nuclear legacy.

Part of that $200m went to the construction of the Landysh, an enormous $36m liquid radioactive waste treatment barge anchored at the Zvezda decommissioning point near Vladivostok. Since its commissioning in 2001, it has processed 800 tonnes of irradiated liquid waste from submarines, according to experts at the Centre for Non-Proliferation Studies in Monterey, California.

Russia and Japan have had their fallings-out, however, and last spring, Japan suspended funding for nuclear remediation projects in Russias Far East over bureaucratic sluggishness and confusion in Moscow. But the Japanese committee reopened its funding gates after a January summit between Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizuimi and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Since the G-8s announcement, everyone is trying to implement projects with Russia, and not just with submarines, the Japanese government official said. We are taking the same approach—we are willing to work on various projects with Russia.

Among projects that Japanese officials have long considered is investing in the rehabilitation of a branch segment of Russia’s impoverished Far East railroads, which are responsible for shipping spent nuclear fuel to Mayak in the Ural Mountains. Others may include building safer temporary land-based storage facilities, as well as further submarine dismantlement, Japanese officials have said.

They have stressed, however, that the Japan-Russia Committees remaining $145m have not yet been allocated to any particular projects. Tokyo invited Russia to avail itself of the remaining money.

Britain Pledges $56M for Sub Cleanup and Joins AMEC

Perhaps the widest-ranging environmental funding announcement came from Great Britain, on June 27th. Britain is not only contributing $36m to dismantle the Northern Fleets two remaining retired Oscar I class cruise missile submarines, but also to pay for improved and safer storage facilities for tonnes of SNF in the Arkhangelsk region. Some of the funding will also be channelled into cleaning up the notorious Andreyeva Bay, where SNF and other radioactive waste from submarines lay in an open dump.

Tackling weapons of mass destruction proliferation is one of this governments highest priorities, Britains Foreign Secretary Jack Straw said of the new commitments—which were finalised during Russian President Putins state visit to Britain earlier this month—in a statement to Bellona Web. Our cooperation with Russia on dealing with its nuclear legacy is a crucial part of this.

As in the contracts with Norway and Japan, Britain stipulated that Russia bear itself any reprocessing costs associated with the submarines dismantlement, said Jane Stevens, a spokeswoman for the British Foreign Office in a telephone interview with Bellona Web. The submarines will be dismantled at Severodvinsks Sevmash shipyard, she said. Britain also donated approximately $20m to NDEP, Trish ODonnell, also of the British Foreign Office, said in a statement provided to Bellona Web.

Britains financial outlay comes as part of its commitment to the G-8 Global Partnership programme, both Minatoms Antipov and the British Foreign Offices ODonnell said.

Britain has also joined the Arctic Military Environmental Cooperation, or AMEC, programme, which addresses military-related environmental concerns in Russias Arctic region. AMECs current members are Russia, Norway and the United States, and its key focus since its inception in 1996 has been to develop nuclear waste storage technologies to improve the overburdened process of storing the tonnes of solid radioactive waste produced by dismantling submarines in Russias Northern Fleet.

Our entry into AMEC will provide significant cooperation and opportunities for the British Ministry of Defence-sponsored naval cooperation with Russia and will enable further projects providing practical assistance to address the nuclear legacy of the Cold War, ODonnell said in her statement to Bellona Web.

The new agreements also come at a propitious time for the debt-ridden, state-owned nuclear giant British Nuclear Fuels, or BNFL, which runs Britains nuclear cleanup operations as well as reprocesses spent nuclear fuel.

Last week, British Secretary of State for Trade and Industry Patricia Hewitt abandoned plans to partially privatise BNFL on the grounds of its poor management and mounting billion-dollar debts caused by reprocessing problems. In response, BNFLs chairman Hugh Collum said the company would seek more involvement in the nuclear cleanup sector.

Dismantling nuclear submarines and making safe spent nuclear fuel are among Russias highest priorities in dealing with the legacy of the Cold War. This is difficult, complicated work, in which the UK can offer real experience, Hewitt said in a statement to Bellona Web.

Not only does this project offer proliferation and environmental benefits, she added, but it also presents future business opportunities for UK companies with nuclear cleanup experience.

France and Canada

Frances donation of $40m to the NDEP account at EBRD is earmarked exclusively for Northwest Russias nuclear cleanup projects. But Bernard Soyer, advisor on nuclear issues at the French Embassy in Moscow, reached this week by telephone, said he would not comment on how France would dictate that the money be spent—be it on submarine decommissioning or SNF cleanup and storage.

All the funding is intended for nuclear projects in Russias Northwest, he told Bellona Web through an interpreter, but that is all I can say.

EBRDs Novak said that Canadas formal drafting of its $21.3m donation to the NDEP fund was still in the works, but expected by weeks end. Novak said that Canada, too, has not earmarked any of its contribution for specific projects, and that the new donations will be channelled at the September or October meeting of the contributors.

Because of all this funding activity, said Novak, we will now see other bilateral nuclear cleanup agreements and more G-8 agreements to rid Russia of its nuclear contamination.

The Board of the Bellona Foundation has appointed former Minister of Climate and the Environment Sveinung Rotevatn as Managing Director of Bellona No...

Økokrim, Norway’s authority for investigating and prosecuting economic and environmental crime, has imposed a record fine on Equinor following a comp...

Our op-ed originally appeared in The Moscow Times. For more than three decades, Russia has been burdened with the remains of the Soviet ...

The United Nation’s COP30 global climate negotiations in Belém, Brazil ended this weekend with a watered-down resolution that failed to halt deforest...