The system built to manage Russia’s nuclear legacy is crumbling, our new report shows

Our op-ed originally appeared in The Moscow Times. For more than three decades, Russia has been burdened with the remains of the Soviet ...

News

Publish date: February 25, 2005

Written by: Charles Digges

News

Analysis

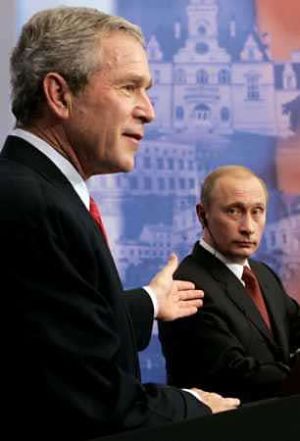

It was something of a surprise, said many State Department and US government officials who spoke to Bellona Web Thursday evening following the summits close, as non-proliferation was one common talking point the two presidents could have made binding progress on at this otherwise often prickly summit.

Hazy nuclear agreement reached

Bush, however, spoke favourably, if vaguely, of the nuclear issues he discussed with Putin, saying at the presidents joint press conference: "We agreed to accelerate our work to protect nuclear weapons and materials both in our two nations and around the world."

In the end, a sideline deal was inked to improve security at Russian nuclear sites where material enticing to terrorists is stored. Both presidents also agreed that Iran and North Korea should not be allowed to develop nuclear weapons, though neither outlined clear steps toward achieving this goal.

"We agreed that Iran should not have a nuclear weapon. I appreciate Vladimir’s understanding on that," Bush said. "We agreed that North Korea should not have a nuclear weapon."

Indeed, Putin remained steadfast in Russias commitment to aiding Irans growing civilian nuclear infrastructure, and he said he still believed the Islamic Republic was incapable of producing nuclear weapons, press reports said, even though mounting evidence contradicts the Russian Presidents assertion.

Furthermore, the nuclear agreement drafted at the summit has clear limitations. Much of it is a reaffirmation of longstanding policy—such as the US Deparment of Energys Materials Protection, Control and Accounting (MPC&A) programmes, and a similar programme run by the US Department of Defence. And while the agreement it proposes accelerating security upgrades at nuclear facilities, it does not mandate completing the work before both men’s terms expire in 2008, as American officials had hoped.

"It is welcome news that Presidents Bush and Putin are talking about how to prevent nuclear terrorism," Ken Luongo, executive director of the Russian American Nuclear Security Advisory Council, an NGO that advises Washington and Moscow on nuclear policy, said.

Luongo added, though, that "it is unfortunate that there were no major breakthroughs on the impediments that are hobbling the realisation of their nuclear security goals—the disputes over access to facilities, transparency, and liability protections. Deadly terrorists are seeking WMD and they are not waiting."

Bush said he talked with Putin at length of his "concerns about Russia’s commitment in fulfilling these universal principles" common to all democracies — such as the rule of law, protection of minorities and viable political debate.

Putin was somewhat recalcitrant when pressed by reporters on Russias recent back-peddaling on Western-style democracy.

"Russia has made its choice in favor of democracy. It has done so for the past 14 years and requires no help from the outside, he said with thinly disguised irritation. This is our final choice and we have no way back. There can be no return to what we used to have."

What does Russia have in terms of democracy and environmental rights?

Last Spring saw a vertically structured power shift that stripped Russias nuclear regulatory body, now part of a body known as The Federal Service for Ecology, Techology, and Atomic Energy (FSETAN in its Russian acronym).

The head of FSETANs nuclear division is Andrei Malyshev, a recruit from the former Ministry of Atomic Energy—known after the spring shake-up as the Federal Agency for Atomic Energy (Rosatom). Rosatoms mandate—like FSETANs—is still unclear, but it has stepped in to fulfil the roll played by its predecessor, even though many of these responsibilities do not legally fall within its realm.

It is safe to say, therefore, that Russia has neither an independent nuclear regulatory body, nor the democratic soil from which such an organisation must spring.

Our op-ed originally appeared in The Moscow Times. For more than three decades, Russia has been burdened with the remains of the Soviet ...

The United Nation’s COP30 global climate negotiations in Belém, Brazil ended this weekend with a watered-down resolution that failed to halt deforest...

For more than a week now — beginning September 23 — the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP) has remained disconnected from Ukraine’s national pow...

Bellona has taken part in preparing the The World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2025 and will participate in the report’s global launch in Rome on September 22nd.