New Managing Director for Bellona Norway

The Board of the Bellona Foundation has appointed former Minister of Climate and the Environment Sveinung Rotevatn as Managing Director of Bellona No...

News

Publish date: February 24, 2003

Written by: Charles Digges

News

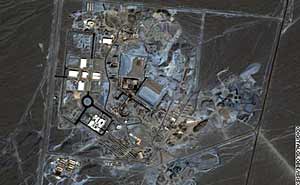

The uranium enrichment site, near the city of Nantanz, was visited Friday by Dr Mohamed ElBaradei, the chief inspector for the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency, or IAEA, who led a small delegation on a long-awaited visit to Iran to assess the status of its nuclear programme. It was the first time inspectors have visited the facility, which was first revealed publicly in December, when the Pentagon showed commercial satellite photos of the site.

During the visit to the Nantanz plant, ElBaradei said inspectors found that it included a small network of centrifuges for enriching uranium. Officials also said they learned that Iran has the capability to make additional centrifuges. Iran last week publicized that it was mining uranium ore near the city of Yazd, and the existence of the enrichment centrifuges essentially gives Iran full control over nuclear fuel cycle technologies it says it is employing for peaceful, energy-producing purposes.

American officials believe the Nantanz plant is part of a long-suspected nuclear weapons programme — a programme that US defence and intelligence circles say has benefited from Russian and Pakistani know-how.

These officials assert that Iran’s aim is to mine or purchase uranium, process the ore and enrich it to levels that would be suitable for the manufacture of nuclear weapons. Tehran’s admitted uranium mines, plus the confirmation of the centrifuges at Nantanz, would give Iran a largely indigenous capability to make nuclear weapons, Washington officials fear.

American chief arms negotiator to Moscow

The US State Department this week will dispatch its chief arms negotiator, Undersecretary of State John Bolton, to Moscow for more talks with Russian nuclear officials to dissuade them from further assisting Iran’s nuclear programme. At present, Russia’s Ministry of Atomic Energy, or Minatom, is building a hotly contested, $800m, 1000-megawatt light water reactor in the Iranian port of Bushehr that is scheduled to start running in late 2003 or early 2004. Last week, Minatom said it will offer to build a second reactor there.

Moscow has also asserted its interest in building as many as four more reactors over the next ten years in Iran, but Washington has charged that Russian expertise is being applied to weapons development. Pentagon officials, in December, said Moscow is helping with the Nantanz uranium facility and with a heavy water facility near Arak, in central Iran, which was also revealed in December’s satellite photos. Moscow and Tehran have denied Russia’s complicity in the construction of the sites.

As part of an effort to appease Washington’s fears, Moscow and Iran last month signed contracts stipulating that Russia will be the sole supplier of fuel for the Bushehr reactor, and will also take back the spent nuclear fuel, or SNF, to reduce risks that Iran will reprocess it for weapons-grade plutonium. But Iran’s capabilities to mine and process its own uranium have, from Washington’s perspective, rendered moot Moscow’s assurances about Iranian SNF.

On Friday, Minatom Chief Alexander Rumyantsev told a news conference that "at this time, Iran does not have the capacity to build nuclear weapons," the Associated Press reported.

He again defended Russian assistance as geared to peaceful purposes, saying that Moscow is giving Iran "only technology that is monitored and authorized by the IAEA. I can vouch that construction of an atomic power station with the return of spent fuel to Russia poses no danger."

ElBaradei welcomes Tehran’s effort toward transparency

ElBaradei’s comments on Saturday, at a press conference prior to leaving Iran a day ahead of schedule, did not indicate that he thought inspectors had uncovered information that would confirm Washington’s fears, and said the results of the inspection visit — which had been delayed from December to this weekend on Iran’s insistence — showed an increased effort toward transparency by Tehran.

After the Nantanz tour and a meeting with Iranian President Mohamed Khatami, ElBaradei said that Iran had agreed to provide advance notice to the IAEA about the construction of any future nuclear facilities. He also said Iran would consider signing the so-called "Additional Protocol" which would allow the IAEA to inspect undeclared nuclear facilities without prior announcement.

Iran’s agreement to notify the IAEA about future sites and its consideration of the Additional Protocol, said ElBaradei, "is a sign of greater transparency from Iran regarding its nuclear programmes."

IAEA Spokeswoman Melissa Fleming said Saturday that two additional inspectors remained behind after ElBaradei’s departure to inspect the heavy water facility near Arak, as well as another facility in Isfahan, whose purpose is not yet clear.

American and British intelligence services not convinced

The new information about the Nantanz centrifuges, and their apparent capacity to eventually manufacture weapons-grade uranium, comes at an awkward time, both for the IAEA, which is carrying out nuclear weapons inspections in Iraq, and for Washington, which is finalizing its plans for an American-led invasion of Iraq to topple its president, Saddam Hussein. The Bush administration has attempted to justify a potential war in Iraq on the grounds that Hussein is seeking nuclear weapons, an assertion that the IAEA, after numerous inspections, has not confirmed.

Bush’s critics, who underscore that nuclear programmes in North Korea and Iran are far ahead of that in Iraq, have said the US administration is focusing too heavily on a much less significant nuclear proliferation threat from Baghdad.

Even prior to the Pentagon’s December release of satellite photos of the Nantanz site, the facility has long been a concern to American intelligence officials, who have concluded that Iran was building a large gas centrifuge plant there to enrich uranium.

The plant under construction in Nantanz has thick concrete walls and is being built underground as an apparent precaution against a military attack. After the disclosure of the satellite photos, ElBaradei requested that it be included in his visit to Iran.

Further steps in Iranian nuclear programme

American and British intelligence services, who spoke with the New York Times, believe Iran’s program would work as follows: Iran would mine natural uranium at domestic sites or buy it abroad. The uranium would then be taken to the facility at Isfahan, where they believe it would be converted into uranium hexafluoride.

This fuel would then be taken either to the centrifuge facility at Nantanz or, perhaps, to some covert centrifuge plant. The progress that Iran has made in centrifuge technology, as documented by ElBaradei’s visit, reinforces concerns that Iran is moving forward in this major area of a nuclear cycle.

Iran says Nantanz will be used to produce low-enriched uranium for civilian power plants that it has yet to build. The Bushehr plant would not need low-enriched uranium from Nantanz because Russia is supplying the fuel.

Iran also says the Nantanz facility will be under international safeguards, which means monitoring equipment will be installed and regular inspections carried out to ensure that no enriched uranium is diverted to non-peaceful purposes.

But the intelligence officials speaking with the Times had several concerns. One is that if Iran is able to build a supposedly civilian enrichment plant in Nantanz, it may as well develop a clandestine nuclear enrichment plant elsewhere. Another is that Iran might somehow divert material from Nantanz and take it to a secret centrifuge plant for enrichment to weapons-grade material.

Still another concern is that Iran will complete the Nantanz plant under international inspection but then withdraw from the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty, which it is legally allowed to do with three months’ notice. It could then reconfigure the installation to make weapons-grade uranium. A rule of thumb, the officials said, is that it takes 1,000 centrifuges of the type Iran is using to make a bomb’s worth of fissile material per year.

A pressing question Washington officials want to have answered is whether Iran has already run some uranium hexafluoride through the small network of centrifuges at Nantanz. This process would yield small amounts of low-enriched uranium, but would be in violation of Iran’s obligations under the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty. Those obligations require that the production of nuclear material be reported.

Nantanz is "an effort to develop a nuclear weapons breakout capability"

An IAEA spokesman questioned about the Nantanz centrifuges would not comment. But Gary Samore, director of studies at the International Institute for Strategic Studies and a former non-proliferation expert with the Clinton Administration’s National Security Council told the Times that "Iran will attempt to justify Nantanz as part of its civilian nuclear power programme, but it is actually an effort to develop a nuclear weapons breakout capability."

"It makes no technical sense for Iran to do this for civilian purposes because Russia has agreed to provide lifetime fuel services for Iran’s only nuclear power plant under construction, the one at Bushehr," Samore added.

"The Iranians will argue that they have plans to buy an additional four or five plants from Russia. But it would make more economic and technical sense for Russia to provide the fuel for those plants," he said.

Last week, an Iranian exile group called National Council of Resistance of Iran asserted at a press conference backed by the Bush administration that research and testing on centrifuge technology was being carried out at a front company near Tehran called the Kola Electric Company. Iran says the company is a watch factory.

The Board of the Bellona Foundation has appointed former Minister of Climate and the Environment Sveinung Rotevatn as Managing Director of Bellona No...

Økokrim, Norway’s authority for investigating and prosecuting economic and environmental crime, has imposed a record fine on Equinor following a comp...

Our op-ed originally appeared in The Moscow Times. For more than three decades, Russia has been burdened with the remains of the Soviet ...

The United Nation’s COP30 global climate negotiations in Belém, Brazil ended this weekend with a watered-down resolution that failed to halt deforest...