Norway’s environmental prosecutor fines Equinor a record amount following Bellona complaint

Økokrim, Norway’s authority for investigating and prosecuting economic and environmental crime, has imposed a record fine on Equinor following a comp...

News

Publish date: April 27, 2015

News

The saws have finally come out to dismantle the Lepse, Russia’s most dangerous nuclear vessel, making way for removal of the potent radioactive threats lying in its holds.

The new developments in actually cutting away the stern of vessel represent a major advance toward beginning to secure its more radioactive compartments in a project that has been fraught with delays, and more than two decades of urgency to remove one of Northwest Russia’s most threatening nuclear hazards.

If things proceed according to schedule, the now-removed stern section will be disposed of. The more delicate work of dealing with the four remaining sections of the vessel is scheduled to begin in autumn.

According to a joint conference in late April between Bellona and Russian state corporation Rosatom, construction of a special radiation shielding box around the vessel’s remaining sections is underway.

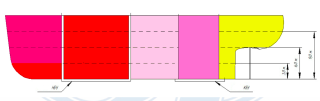

The plan for disposing of the Lepse envisions cutting the ship into 5 sections moving toward the bow, the second and fourth sections of which contain the bulk of the vessel’s long-stored spent nuclear fuel.

The highly sensitive dismantlement work is being undertaken at the Nerpa naval shipyard north of Murmansk.

Officials say the Lepse’s holds are loaded with 639 spent nuclear fuel assemblies, many of which are damaged and will require as-yet-to-be-developed technologies to safely remove.

Alexander Nikitin, chairman of the Environmental Rights Center (ERC) Bellona, said the next section of the vessel will be treated and sent to Sayda Bay, where construction of a conditioning facility for solid radioactive waste has been underway.

The third section – or midsection of the vessel – contains no harmful spent nuclear fuel, and will be scrapped, said Nikitin.

The forth section up, however, will require immense effort and construction of shelter at Nerpa against radiation. This shelter will serve as operational headquarters for unloading all spent nuclear fuel stored aboard the Lepse,

Nikitin said that because the spent nuclear fuel came from icebreakers – most notably the now-retired Lenin – it will be the responsibility of Atomflot, Russia’s nuclear icebreaker port, to develop the technology and removal plans. The entire project, as presented at the joint seminar, is scheduled for completion by 2017.

But Nikitin said that extracting the nuclear fuel assemblies from the problematic fourth section would have to proceed on a case-by-case basis.

“Undamaged fuel can be removed by standard methods,” he said, “But assemblies that were damaged in unloading operations will require specialized approaches.”

The damage to the fuel elements occurred in 1965 and 1967, when coolant leaks in the Lenin’s reactors deformed them, making their extraction for storage impossible by conventional means.

“Whether engineers are able to develop special robots for the removal of this fuel in time or not is something that might push back the full completion date,” for the dismantlement, said Nikitin. “This is very sensitive work with high risks of radiation exposure that have never been tried before.”

All other aspects of the dismantlement program are, for the time being, running according to schedule, he said. Once complete, the nuclear fuel will be sent to the southern Urals’ Mayak Chemical Combine for reprocessing.

The Lepse’s long, problematic history

The Lespe, which was built in 1934, served as a floating unloading point for spent nuclear fuel from Soviet Icebreakers between 1961 and 1988. That year, it was retired from servicing nuclear icebreakers docked at Murmansk’s Atomflot icebreaker port.

After it was taken out of commission, it spent 24 years bobbing at dockside at, Atomflot, a mere 20 kilometers from the center of Murmansk and its 300,000 residents, posing a major radiological hazard.

In 1994, the vessel and the dangers it posed caught Bellona’s eye, according to Bellona Executive Director and nuclear physicist Nils Bøhmer. The organization mobilized the European Union to allocate funding toward removing it from Murmansk harbor and safely dismantling it.

In September 2012, the Lepse was finally towed from its berth at Atomflot, but ran into two years of traffic jams at Nerpa while the Ministry of Defense and Rosatom wrangled for dry dock space, which, at the time, was taken up by the Leninsky Komsomol, Russia’s first nuclear submarine.

Those difficulties were finally resolved in October, when the Lepse was gingerly moved from the water to dry dock.

The Leninsky Komsomol, which had already been cut into three pieces, is being welded back together as a museum piece.

Økokrim, Norway’s authority for investigating and prosecuting economic and environmental crime, has imposed a record fine on Equinor following a comp...

Our op-ed originally appeared in The Moscow Times. For more than three decades, Russia has been burdened with the remains of the Soviet ...

The United Nation’s COP30 global climate negotiations in Belém, Brazil ended this weekend with a watered-down resolution that failed to halt deforest...

For more than a week now — beginning September 23 — the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP) has remained disconnected from Ukraine’s national pow...