Arctic Frontiers: Disinformation, Security and the Northern Sea Route

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

News

Publish date: March 27, 2015

News

THE NATURE COAST, Florida – A group of fishermen living along Florida’s “Nature Coast” – tucked along the state’s western shore from the Panhandle to Pine Island – have agreed to meet with Bellona’s Karl Kristensen and me and they’re feeling a bit edgy.

We’ve driven out to a house out along the Gulf of Mexico through the early sunset of a late February night.

All of them have switched off their cellphones. A woman paces back and forth to the edge of the yard to monitor passing cars and gauge if our voices might carry over the still sea waters where prying ears could be listening from darkened boats.

The people at the house are trying to puzzle together the four most devastating events following BP’s Macondo well blowout on April 20, 2010, which killed 11 and fouled Gulf waters with 4.9 million barrels of crude: declining and deformed seafood harvests, chronic illnesses they’ve developed, what’s happening to the environment that provides their livelihood, and why their concerns are met with foreboding hostility and ominous threats.

Unlike other interviews I’ve had with Deepwater Horizon victims in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama – who all talked to me in public lunch shacks or on their docks – this discussion opens with one of the fishermen telling me: “We could get killed for what we are telling you.”

The fishing community in which they live is small and insular, they explain, and solely dependent on the sea for its survival. Talking about how it was impacted by the BP oil spill is violently discouraged.

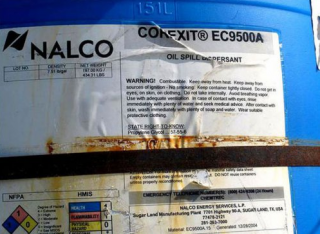

One of the group says the message to many in these small fishing villages is clear: “If you’ve got something to say about oil or [the toxic oil dispersant] Corexit affecting these waters, keep your mouth shut.”

He recounts the retribution he’s seen, and that might await anyone sitting in the dim ring of the porch’s light.

“You get your [car’s] gas tank sugared, houses burn, people get followed by unmarked vans and trucks, people disappear,” he says. “There’s the little stuff that just messes with people’s livelihoods, can’t get to work, can’t fix your boat, and then there’s the big shut up – the threat is very real, and people’s lives are in danger.”

Shanna Devine is with the Government Accountability Project (GAP), America’s premier whistleblower protection group. She has catalogued the health and welfare of the post BP Gulf community, and told me these anonymous accounts square with dozens she’s documented.

“Many people who have reported to us say they’ve seen the same kind of thing – nondescript vans associated with security type agencies, and tails,” Devine told me. “A lot of the sworn affidavits we have confirm this kind of harassment.”

Even though such reports may sound like grist for the conspiracy mill, Dr Riki Ott, an eminent marine toxicologist and survivor of 1989’s Exxon Valdez disaster, says threats in the wake of the Exxon Valdez and the Deepwater Horizon have been documented so widely and with too much credibility to be dismissed.

“These things really happen,” she told me in a telephone interview. “The government is supposed to protect us from threats like this, but continued harassment on the Gulf demonstrates a police state mentality.”

BP has said in statements that it employed the enormous security firm Wakenhut to handle facilities and cleanup security during the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Wakenhut’s board was comprised largely of former CIA, FBI and Pentagon officials.

William Hinshaw, a retired FBI agent told Al Jazeera in 2011, that, “It is known throughout the industry that if you want a dirty job done, call Wackenhut.”

Forced to deny the obvious

Forcing the Nature Coast community to deny that the spill haunts its waters by using the violent threats, stalking campaigns and financial ruin seems pointless.

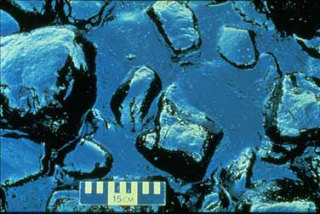

On February 23 Kristensen and I dug up weathered oil on a beach 300 kilometers north of here that a Tampa area marine biologist fingerprinted to the blown out Macondo well. The scientist requested anonymity for fear of personal and professional reprisals. Another sample of the same oil will be tested at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Chris Topping, president of the Clamtastic clam fishery on the Nature Coast island of Ceder Key told me in a telephone interview that his company receives BP liability payouts to recoup their losses, proving that even the oil giant acknowledges local damages.

He pointed out that his clam harvests have gone up and down with seed availability, and wished to state that he didn’t think his product’s health has been hurt by the spill. But he is curious about some developments at sea he’s never seen before.

Maps from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) don’t show this area of Florida was hit by oil. But numerous studies since the initial disaster show that oil and dispersant did wash up here and continues to do so.

Topping told me that, “Right after they said they stopped the spill [in July 2010] you could smell the oil around here.”

Witnesses gathered at the remote house confirm this. Each of them add that they were hit by Corexit sprayed from planes in 2011, and in some cases into 2012 and 2013, well after the Coast Guard stopped official Unified Command sprays and sub sea Corexit applications at the Macondo wellhead in July, 2010.

And each of the witnesses exhibits symptoms that clearly mark them as casualties of the BP disaster. Local doctors are reluctant to treat them. One woman present with us, who pushed to have her rashes and respiratory difficulties diagnosed, was told by her doctor that, “If you get me into a lawsuit against BP, I am leaving the country.”

One of the clam fishermen with us has suffered severe impacts to his neurological functions connected with oil and Corexit exposure and speaks from prepared notes. His doctors haven’t suggested an MRI, which medical experts I’ve spoken to say might reveal symptoms akin to those seen in spill victims in other states. But such diagnostic techniques are not offered at a local level.

Tell tale sea change

And there’s something about the local sea environment that’s just not right.

Over the summer, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) said the region experienced the longest red tide, or harmful algae bloom, in nearly 10 years. Topping said red tides are exceedingly rare on this part of the Florida coast.

The gathered fishermen say it wasn’t a red tide at all.

“It was clear,” says one of the oyster fishers. “Usually it’s kind of murky and red because of the algae, but this was different.”

Topping and the fishermen also say they’re deviled by an invasive sea grass they’ve never seen growing on their clam leases.

Insufficient science

In his interview with me, Topping said: “Are we seeing these changes in the environment due to the spill? Only time will tell.”

Something that might help speed the clock is a broader scientific effort by state agencies to get to the bottom of things.

Mike Smith, the operations manager at Ceder Key Aquaculture Farms told me in a separate interview that he’s satisfied with the Florida Department of Aquaculture and Consumer Service’s efforts to monitor water, samples of which, he told me in a telephone interview, the agency does every day.

But Jill Fleiger in the agency’s aquaculture lab in Tallassee not only said in a phone interview that sampling was far less frequent, but added her department wasn’t looking for oil.

“We don’t necessarily look for petroleum pollution, we look for fecal coliform,” she told me.

She said her lab had tested for hydrocarbon baselines in the water directly after the spill five years ago. “The samples that were collected were drawn before oil could have potentially reached any of our shellfish,” she told me.

What those samples showed and whether further ones were taken to compare to the unoiled baseline is unknown to Fleiger, who referred me to the Florida Department of Aquaculture and Consumer Service’s department of food safety. There, I was told that no one with any knowledge of the samples could be located for comment.

Peter Frizzell, a retired musician and carpenter who lives on Cedar Key, whose story was detailed in the first article in this series, told me he understands keenly how the fishermen I’ve spoken with feel. He’s lived there for 16 years and counts many of in the fishing community among his friends. Since getting sick in 2011, he’s also become the community’s walking encyclopedia on the spill.

“[The fishermen] are all stuck between a rock and a hard place,” he said in an email interview. “There are those who are still trying to get compensation for their losses from as far back as 2010. Others who did take payouts were also forced by BP to sign releases saying that future litigation was not an option for them once they took the checks.”

But now, said Frizzell, some science is starting to trickle in concerning the long-term effects of the disaster and the unprecedented use of Corexit.

“If that science proves there is indeed a problem, then those that signed off [on BP’s early payouts] will have no recourse,” wrote Frizzell. “Of course BP knew this. This isn’t their first rodeo.”

A typical pattern of harassment

The information blackout on illness, strange sea changes, and oil and Corexit hits that muffle this area bears the hallmark of being orchestrated and enforced.

Accounts published by Devine in GAP’s report Corexit: Deadly Dispersant in Oil Spill Cleanup show those who exhibited symptoms of oil and dispersant illnesses in Louisiana in 2010 and 2011 were routinely spied on, harassed by BP and its subcontractors, suffered home invasions, had their trash searched, and in some cases were run off the road by security-type vehicles, like those who spoke to me in Florida.

Ott has seen it all before.

“People are being followed, their homes are being broken into, homes are being staked out, cell phones are being taken, and people’s lives are being messed with,” she told me. “In general what we are seeing is the same industry and even government harassment on the Gulf that we saw in Alaska – these are total invasions of privacy.”

But she said the ante has gone up since the Exxon Valdez spill in 1989 thanks to the internet and social media.

“Facebook, Twitter, and all of these things at our disposal at an instant allow for immediate publication of harassment,” Ott said. “But it also increases the number of people who can be targeted – in Alaska we knew of a hundreds of people who were getting threatened, where in the Gulf, we know of thousands.”

Because of new technology, one popular intimidation method on the Gulf is swiping smartphone devices, said Ott. She said she was aware of several incidents when police in Gulf states had pulled over whistleblowers and separated them from their cars and cell phones on various trumped up suspicions.

“Tactics like this allow access to their SIM cards and information on their contacts, and this was done by state troopers and even government agencies,” she said. “And with those contacts, the net of harassment spread.”

Military support for hire to the oil industry

The oil industry and the Wakenhut security firm, which subsequently became G4S USA, have long been cozy bedfellows.

The company website says G4S USA provides military-level protection to the US’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve, the Alaskan oil pipeline, nuclear-weapons facilities, nuclear reactors, and Cape Canaveral. G4S’s home offices are in the UK, and works in more than 120 countries. It has 59,000 employees in the US

Its US division also runs 32 private detention facilities for juveniles primarily in the American South and Southwest, despite documentation that arose in 1999 of Wakenhut’s pervasive abuse of inmates in two prisons they ran in Texas and New Mexico.

Sinister echoes of Alaska

Ott told me Wakenhut worked for BP and Exxon/Mobile to spy on whistleblowers documenting safety problems along the 800-mile-long Alyeska pipeline in Alaska. Wakenhut singled out oil industry whistleblower Chuck Hamel, who tipped off Congress about the pipeline’s issues in 1991.

Hamel won an invasion of privacy lawsuit against Alyeska in 1993, and the pipeline operator admitted it hired Wakenhut to secretly tape his phone calls, search his mail, garbage, phone and credit card records, and set up bogus environmental groups to shake discrediting information out of him and other whisteblowers. The firm also spied on former California Congressman Robert Miller, a fierce critic of the oil industry.

The case was the subject of Congressional hearings and is public record. Wakenhut’s broad espionage campaign is documented in a US Congressional report called “Alyeska Pipeline Service Company covert operation : report of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs of the U.S. House of Representatives, One Hundred Second Congress, second session.”

BP has acknowledged that it hired Wakenhut for security purposes during the Deepwater Horizon disaster, though denied the firm was used for intimidation.

In a statement, BP wrote that, “Wackenhut, which as of 2014 still maintained five locations along the Gulf Coast” was employed to “provide fixed security where we housed equipment used for cleanup activities.”

“They have not and do not conduct surveillance activities as part of their security role,” the statement continued. “Any allegations that BP is involved with harassment of citizens are unfounded and irresponsible.”

Wackenhut also provided security for the Deepwater Horizon Unified Command during the oil disaster. BP along with the US Coast Guard, NOAA and other government agencies ran Unified Command.

G4S USA would not respond to several requests for comment on its predecessor Wakenhut’s security mandate during and after the BP disaster.

The G4S USA’s website’s section that outlines its services for the oil and gas industry reads in part that: “We understand the industry and we are able to draw on our expertise, our proven capabilities in risk assessment and intelligence […] and integrated technology solutions to deliver effective, comprehensive security solutions.”

Shooting the messengers

Independent scientists who work neither for BP nor the National Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) have long said they’ve been locked out of critical research sites by state and federal agencies, or BP itself.

BP has obvious interests in producing a certain kind of data because of the ongoing $13.7 billion federal lawsuit against it. On March 16 BP published a widely ridiculed report called “Gulf of Mexico Environmental Recovery and Restoration,” which claimed “areas that were affected are recovering” and that its studies “do not indicate a significant long-term impact to the population of any Gulf species.”

NOAA called the report “inappropriate” and “premature.” But NOAA is also speaking for the NRDA.

The NRDA offers few opportunities for publishing timely, objective science, Louisiana State University entomologist Linda Hooper-Bui told me in a telephone interview. The NDRA is run by the US government, state agencies and BP to identify the natural resource damages resulting from the catastrophe, as well how to restore wrecked resources, and how much money is required to do so.

Agencies working on the NRDA are supposed to keep their results confidential until the study is complete. It presently has no deadline.

“That’s an impossible position to put scientist in, especially if we have information that should be known now,” said Hooper-Bui. “I don’t want our science locked up and kept out of sight for what could be the next 10 years.”

Immediately after the spill, she and her research team were prevented from measuring the impact of the oil disaster on spiders and insects in certain areas of Louisiana’s oil drenched wetlands and shores.

“BP was desperately trying to control the science,” she said. Someone she identified as BP’s chief science officer attempted to intimidate her, and BP workers “bullied’ her research staff and threatened her with arrest.

“Local sheriffs who said they were working for BP, people from Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries, the Coast Guard, all of these groups working under BP kept us from doing our job, even stopping us from going into areas were we had ongoing studies,” she said.

She reacted by making BP’s restrictions public in an op-ed piece in the New York Times. The morning the piece ran, BP’s science officer was back on the phone with her, offering her money to stay quiet.

But the op-ed piece seems to have hit the mark. “The BP and the NRDA people backed off relatively quickly,” she said. “And we got back to work.”

BP refused to comment on Hooper-Bui’s case.

Robert Naman, chief chemist with Analytical Chemical Testing lab in Mobile, Alabama, has spent the last several years running independent fingerprints of Macondo well oil.

He’s publicized his results and submitted over 1000 samples to NOAA and the EPA, all of which were rejected, he told me, “because they’re not telling the scientific story the government agencies wants to see.”

But his studies still caught their attention.

“In late 2011 or early 2012, a bunch of guys who said they were from NOAA came and basically camped out outside my lab,” he told me by phone. “They said they wanted to come in and have a look around, but I didn’t let them in.

“Still,” he said, “they stuck around outside for the rest of the day.”

Hooper-Bui said her first response when anyone tries to obstruct her work is to go public.

“I go directly to the press, publicize what’s going on and tell them ‘don’t f*ck with me,’” she said. “I also let everyone know what I am up to – I talk to the sheriffs and mayors and let them know exactly what we’re doing, and tell them they can read our studies, and that we’re conducting honest science and have nothing to hide.”

Terrorizing the online community

It remains unclear who’s behind campaigns that sought to terrorize hundreds of online critics who posted to BP America’s Facebook page, which is run by American advertising giant Oglivy & Mather.

One woman I interviewed who was harassed over a three-year period both on and off BP’s page asked I refer to her as “the whistleblower,” for fear of “further retribution from BP trolls.”

A troll is Internet jargon for someone who sows online discord by starting arguments and upsetting people in discussion groups by posting inflammatory messages. In the case of BP America’s Facebook pages, the whistleblower told me, these messages turned into death threats.

Over a three year period, from the initial spill to 2013 the whistleblower documented all manner of threats like identifying where critics lived, making references to owning guns and using them on BP critics, and other derogatory, sexist and racist remarks, and legal threats.

“One troll told me he wanted to ‘put a bullet between my eyes,’” the whistleblower told me. “Another called me a ‘truck stop street walker with a social disease.”

Among the documents and screenshots supplied by the whistleblower was one showing a troll called “Griffin” suggesting he’d use gun violence. Griffin also superimposed the crosshairs of a rifle scope over one BP critic’s pet bird. He further posted photos of an arsenal of semi-automatic weapons.

The whistleblower said trolls dug into critics’ family photos to create false Facebook profiles.

GAP’s Devine investigated the whistleblower’s case and received an answer from BP’s ombudsman. The letter, dated December 18, 2012, and shown to me by Devine, stated that, “BP America contracts management of its Facebook page to Ogilvy Public Relations” and added, “Ogilvy manages all of BP America’s social media matters.”

Devine sent a second inquiry regarding the connections some of the trolls seemed to have to BP and Ogilvy, but the ombudsman wrote back that those “request[s are] out of scope for the purposes of this case.”

The whistleblower said the attacks finally abated in late 2013, but that some of the familiar trolls still continued to menace BP protest pages. It’s difficult to connect them to either the oil giant or their PR firm.

“Since an investigation was initiated by the [BP] ombudsman, the trolls might have just left for fear of discovery, so it’s not conclusive whether they were actually connected to BP,” said Devine.

Shirley Tillman, 65, who took part in BP’s Vessels of Opportunity (VOO) program, which paid Gulf fishermen to help clean up the oil spill, didn’t even have to go onto BP’s page to find herself a subject of fierce derision in its comment threads.

While participating in the VOO program, she took hundreds of photos of Corexit sprays and dead sea life along the beaches of her hometown, Pass Christian, Mississippi. She posted the photos on an independent website and then heard through friends that BP America page trolls were calling them phony.

“I took pictures of 35 dead Kemps Ridley turtles on the beaches between Long Beach [Mississippi] and Bay St. Louis [Mississippi],” a distance of about 15 miles, she told me. She was accused on BP America’s page of dragging the same dead turtle to different spots and photographing it.

She said further that two of her Facebook friends received harassing telephone calls as a result of her photographs.

Tillman and her husband are still suffering from illnesses related to their exposure to oil and Corexit. But neither became so ill as their grandson, who was at the time 5 years old. He was turned away for treatment at hospitals in Mississippi and Louisiana. It wasn’t until he was taken to a Florida doctor that his parents got an accurate picture of the volatile organic compounds in their systems – all of which corresponded to chemicals associated with the spill.

How can gulf residents speak freely?

Whoever is responsible for trying to cow the Gulf community into silence over the spill, said Hallstein Havåg, Bellona’s director of policy and research, is violating basic human rights.

“Those behind these actions are committing serious abuses against ordinary rights to free speech and are spreading uncertainty about American citizens’ legal rights,” Havåg said. ”Bellona has a long history of assisting whistleblowers against the oil industry” he said, adding that ”people who contribute important disclosures about environmental crimes are the heroes of our time.”

But stepping up to be one of these heroes is a daunting prospect.

Like Professor Hooper-Bui, Ott can’t stress enough the importance of raising one’s voice in the face of threats.

“If people can speak in a unified voice and say ‘we’re not going to take it,’ in my case, that eventually got them off my back,” she told me. “These are shadowy forces that pretty much cringe at being exposed to the daylight. The best thing to do is to bring them forward and make noise in the media.”

She told me that, “we will never beat these guys at their own game – we need to tell them that this is not acceptable.”

“If we don’t speak out collectively they win,” she added. “I realize it’s scary and can be dangerous, but what kind of country would be living in if we didn’t react?”

This is the second in a series of articles Bellona is producing for the fifth anniversary of the Deepwater Horizon spill.

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

Our December Nuclear Digest, reported by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center, is out now. Here’s a quick taste of three nuclear issues arisin...

Bellona has launched the Oslofjord Kelp Park, a pilot kelp cultivation facility outside Slemmestad, about 30 kilometers southwest of Oslo, aimed at r...

Our November Nuclear Digest by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center is out now. Here’s a quick taste of just three nuclear issues arising in U...