Arctic Frontiers: Disinformation, Security and the Northern Sea Route

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

News

Publish date: February 3, 2020

News

It should have been an easy job. Instead, towing a rust-bucket nuclear submarine known as the k-159 to scrapping ended in a headache Russia has yet to get over.

The sailors had done it dozens of times. Throughout the late 1990s, the Russian Navy, assisted by international partners, had hauled scores of derelict nuclear submarines to successful dismantlement – marking a major step forward in making the world safe from the nuclear relics of the Cold War. But this time, something went terribly wrong.

The sub itself was a perfect example of what Russia was trying to clean up. Launched in 1963, the K-159 had become hopelessly irradiated after a coolant leak in one of its reactors two years later. Over the next decade and a half, the navy tried to restore it to service without success, and in 1989 it was decommissioned altogether.

From then on it sat neglected at the Gremikha base on the eastern edge of the polar Murmansk region, prey to rust, water, and the harsh Arctic elements – its two reactors still loaded with 800 kilograms of aging nuclear fuel.

In 2003, the orders finally came down to send it to scrap at the Polyarny Naval Shipyard, 350 kilometers to the northwest along the Kara Sea. The sub was no longer seaworthy so four pontoons were welded to its corroded hull to keep it afloat during its journey. Ten sailors were stationed aboard the vessel to pump out water and plug up the leaks along the way.

The K-159 prior to its fateful towing.

Credit: Bellona

The K-159 prior to its fateful towing.

Credit: Bellona

In the small hours of the next morning after the K-159’s convoy set sail, a storm hit. Things went bad quickly. The towline running from the tugboat to the K-159 snapped. One of the pontoons was battered loose by waves. Within an hour, the sub foundered. Rescuers were thwarted by wind and high seas. Only one of the sailors aboard the doomed vessel was saved.

Since then it has laid – like so much other Soviet nuclear debris – at a depth of 200 meters beneath the Kara Sea, its aged reactors loaded with uranium fuel, threatening to spill contamination.

But now the Russian government says it’s time to bring it – and thousands of other pieces of radioactive material left on the ocean floor by the Soviet Navy – to the surface.

Over the past 30 years, Russia, with the assistance of numerous foreign governments and hundreds of international experts, has safely disposed of 198 old nuclear submarines that constituted the bulk of the once-feared Soviet Northern Fleet.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the ensuing economic chaos left these sea-faring engines of the Cold War rotting in their ports, still loaded with spent nuclear fuel, in danger of sinking – or worse.

A mammoth multi-year task of engineering and calibrating domestic political will with international political cooperation – much of it fostered by Bellona – has finally made Arctic Russia, and the rest of the world, free from the risks of widespread contamination posed by those subs.

But there is still the Soviet Cold War legacy that lies under the waves – and a similar alchemy of cooperation and funding will be required to bring it up.

Over the course of the past month Bellona’s Alexander Nikitin, who spearheaded the efforts to rid the Arctic of those derelict nuclear subs – has been in discussions with Russian government agencies to do just that.

The new impulse to lift these hazards coincides with Russia’s upcoming chairmanship of the Arctic Council, whose rotating presidency Moscow assumes in 2021. And while the government has discussed raising these nuclear artifacts many times before, there is hope that prioritizing the task within this eight-nation body will give the project the push it needs.

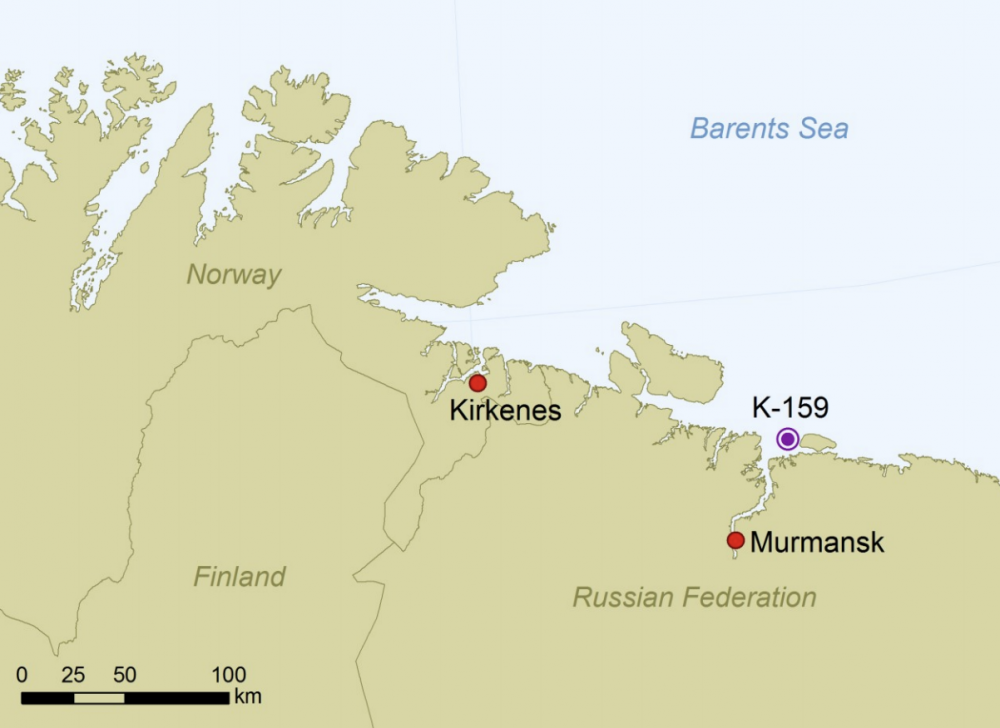

The location of the K-159 sunken nuclear submarine.

Credit: Norwegian Radiation and Nucear Safety Authority

The location of the K-159 sunken nuclear submarine.

Credit: Norwegian Radiation and Nucear Safety Authority

In a sense, the push has already come. For years, member nations of the Arctic Council have demanded to know Moscow’s plans for its sunken nuclear heritage. At present Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs is preparing to answer those demands, and to develop an over-arching master plan for underwater nuclear cleanup as Moscow assumes its new leadership role.

To do that, Rosatom, Russian’s state nuclear corporation and the Ministry for Far Eastern and Arctic Development have launched a series of government discussions that have encompassed numerous experts, including Bellona’s Nikitin.

They will have their work cut out for them. Russia’s Emergency Services Ministry says that some 18,000 pieces of radioactive litter, most of it dumped by the Soviet Navy, have been left in the depths of the Barents and Kara seas off the coast of Murmansk.

Bellona's Alexander Nikitin

Credit: Bellona

Bellona's Alexander Nikitin

Credit: Bellona

Among the finds, according to a catalogue the Russian government released in 2012 are: Some 17,000 containers of radioactive waste; 19 ships containing radioactive waste; 14 nuclear reactors, including five still loaded with spent nuclear fuel; and 735 other piece of radioactively contaminated heavy machinery.

Scientists at the Nuclear Safety Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, or IBRAE, say that time and corrosion have erased thousands of these hazards, leaving about 1,000 that continue to pose high risks of radioactive contamination.

Chief among those are the K-159 and another submarine, the K-27, both of which officials say pose the greatest threat to the environments in which they now lie.

The K-159, in particular, lies in the midst of fertile international fishing waters in the Kara Sea. Should a serious breach in the vessel’s sunken reactors occur, Russian experts estimate that fishing would be banned in the area for at least a month, costing the Russian and Norwegian economies about $120 million. That’s just slightly less than most estimates for raising the vessel.

Unlike the K-159, the K-27 was scuttled intentionally – a nuclear waste dumping practice the Soviet Union had with the United States. Launched in 1962, the K-27 suffered a radiation leak in one of its experimental liquid-metal cooled reactors after just three days at sea. Over the next 10 years, various attempts were made to repair or replace the reactors, but in 1979, the navy gave up and decommissioned the vessel.

Footage taken by a mini-submarine in 2012 of the K-27 submarine's hull.

Credit: Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority

Footage taken by a mini-submarine in 2012 of the K-27 submarine's hull.

Credit: Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority

Like the K-159, the K-27 claimed its share of victims. Nine members of its crew of 144 died of radiation related illnesses shortly after returning to shore. Many more of the crew succumbed to similar illnesses in the years that followed.

Too radioactive to be dismantled conventionally, the Soviet Navy towed the K-27 to the Arctic Novaya Zemlya nuclear testing range in 1982 and scuttled it in one of the archipelago’s fjords at a depth of about 30 meters. The sinking took some effort. The sub was weighed down by concrete and asphalt to secure its reactor and a hole was blown in its aft ballast tank to swamp it. But the fix won’t last forever. The asphalt was only meant to stave off contamination until 2032.

Worse still is that the K-27’s reactors could be in danger of generating an uncontrolled nuclear chain reaction, prompting many experts to demand it be retrieved first.

Raising these submarines from the depths will require technology Russia currently lacks. Even the lifting of the Kursk – perhaps the most famous sub recovery to date – required the assistance of the Dutch. But once these vessels are brought to the surface, the infrastructure that was built to handle those original 198 submarines is robust and available. Now that the political will to raise the subs has once again emerged, it would seem wasteful not to make use of it.

Bellona will continue to urge for the safe disposal of these subs and the other radioactive antiquities of the Cold War. And we hope that ours will be only the first international hands to help.

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

Our December Nuclear Digest, reported by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center, is out now. Here’s a quick taste of three nuclear issues arisin...

Bellona has launched the Oslofjord Kelp Park, a pilot kelp cultivation facility outside Slemmestad, about 30 kilometers southwest of Oslo, aimed at r...

Our November Nuclear Digest by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center is out now. Here’s a quick taste of just three nuclear issues arising in U...