Working to discern patterns of environmental disinformation in an online world

For the past eight years, disinformation has dominated news around elections all over the world. Despite this, it is still a widely misunderstood con...

News

Publish date: December 19, 2002

Written by: Charles Digges

News

The case is the latest example of the Bush administration’s growing difficulties with nations that it has hailed as allies in its efforts against Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups.

Pakistan has been identified by the C.I.A. as both a supplier of nuclear technology to North Korea and a purchaser of North Korean missiles. Yemen took delivery of a shipload of North Korean missiles over the weekend, after the shipment had been seized at sea. President Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney agreed to let it proceed after Yemen’s president angrily told Mr Cheney that the United States had no right to interfere.

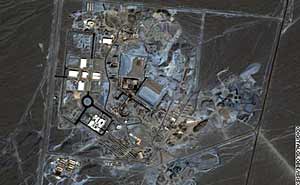

In the first public US evaluation of satellite imagery — commissioned by and broadcast on CNN late last week — of two suspected Iranian nuclear facilities, the White House said it had powerful suspicions about the locations which it said served no energy purpose.

Russia’s atomic energy minister, Alexander Rumyantsev, was quoted by the Russian Itar-Tass news agency on Sunday as contending that Iran had violated no international rules in building the two nuclear sites. The United States responded that it was “deeply concerned” about the two sites, which have been known to American intelligence agencies for more than a year.

Iran has vehemently denied it has a nuclear weapons programme and dismissed concerns about two sites near the towns of Nantanz and Arak. But State Department spokesman Richard Boucher said that “the circumstances of these particular sites are actually fairly interesting and lead to the conclusion that this nuclear programme is not peaceful and it is certainly not transparent.”

Secretary of State Colin Powell added that “we have had conversations with Russia that we are concerned about this and that some of the support they are providing might well go to developing nuclear weapons within Iran.”

“It will continue to be a matter of discussion with us and the Russians.”

Earlier this week, though, officials with Russia’s Ministry of Atomic Energy, or Minatom — which has been building a controversial $800-million light-water reactor at Bushehr, Iran, on the Persian Gulf — issued yet another of its regular statements that its nuclear assistance to Tehran was not military.“To this day, the ministry has received no firm information (from Washington) that Iran had a nuclear programme that contradicts” international agreements, the Interfax-AVN military news agency quoted an unnamed Minatom official as saying. “The technology that Russia supplies to Iran cannot be used for military purposes,” the ministry added.

When President Bush visited Russia in May this year, he was assured by Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, that Moscow was only aiding Iran in the production of nuclear power plants for peaceful purposes. Bush disputed that view, and these differences on Russia’s contracts to assist Iran’s nuclear programme remain a major source of contention in US-Russia relations.

A Defense Department official who has monitored developments at Iranian facilities closely told Bellona Web Tuesday on the condition of anonymity that the Russians were involved “in all aspects of the Iranian nuclear programme,” including the two newly disclosed facilities.

He said Pentagon analysts estimate that with outside help, the Iranian uranium-enrichment programme could produce enough fissile material to manufacture a nuclear device within a few years, but if no outside aid were forthcoming, it could take until the end of the decade.

One of the commercial satellite photographs shows what looks like a heavy-water reactor in Arak, the kind that would be crucial for the production of a plutonium bomb. Another photo, of Nantanz, shows a separate facility for producing highly enriched uranium, another path to producing a nuclear weapon. The imagery showed that portions of the uranium facility will be hidden underground. Like North Korea, which just announced it would restart its plutonium programme, Iran appears to be pursuing the uranium and plutonium options simultaneously.

Though Minatom officials deny outright that Moscow’s nuclear assistance to Iran is military, they have, since the revelation of the satellite images, turned up the volume on their efforts to ensure that Iran signs a commitment to return spent nuclear fuel (SNF) from the Bushehr reactor — which could be reprocessed for plutonium — to Russia.

On Friday, according to Minatom, Nuclear Minister Rumyantsev is scheduled to lead a delegation to Tehran to pick up a signed promise from the Iranian government to return the Bushehr SNF to Russia for storage and eventual reprocessing. The delay of this agreement has been a source of friction between the United States and Russia since it was discovered over the summer that no such agreement had yet been forged between Tehran and Moscow.

When this news was leaked to Greenpeace, however, Rumyantsev made repeated public promises that such an agreement would be signed. But even the agreement he is scheduled to pick up this Friday has been in the hands of the Iranians since October, which indicates to environmental groups — and even some Minatom staff — that securing the return of the SNF and stemming the proliferation threat it would otherwise cause should it remain in Iran has been of secondary importance to Minatom brass.

Bushehr is expected to receive its first fuel shipments in early 2003 and the plant is expected to go online sometime in 2004.

American experts have said in recent years that Iran has skilfully exploited loopholes in the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.

The treaty allows the import of “peaceful” nuclear technology, as long as the International Atomic Energy Agency is permitted to inspect facilities that countries declare as part of their nuclear programme. The agency has conducted regular inspections in Iran. But those have not included secret facilities that Iran has not yet declared, including the sites pictured in the satellite photographs.

Publicly, the Bush administration has been very low-key about the Iranian projects, pointing out that it could be years before they pose a threat. But when speaking with the promise of anonymity, some officials say there is deep concern that terrorist groups could, in their turn, easily obtain nuclear technology or know-how from Iran.

The future of Russia’s nuclear ties to Iran is uncertain. Over the summer the two countries reached an agreement in principle to build as many as five more nuclear power reactors like one already under construction at Bushehr — a deal that could net Minatom as much as $10bn.

A week after the proposals to build more reactors were disclosed, however, Russia appeared to back away from them. After pointed discussions in Moscow with Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham, Rumyantsev suggested for the first time that Russia was prepared to take into account “political factors” before expanding its assistance to Iran.

But Minatom’s commitment to those political factors is equally uncertain. In a bid to end Russia’s nuclear co-operation with Iran, US officials in October offered a potentially lucrative economic deal to Moscow.

The officials told their Russian counterparts that if they cut off all avenues of nuclear co-operation to Iran, the Bush administration would work to lift restrictions on the import of SNF to Russia. Minatom has been trying, with little success, to realize plans to import 20,000 tonnes, or 10 percent, of the global stockpile of SNF by 2020, which would earn Russia $20bn.

The US, however, controls 70 to 90 percent of the world’s SNF and has a commanding veto over what happens to it and where it is stored. For Russia’s import plan to work, then, US backing is essential. Despite that, Russian officials resisted the deal, even though the long-term pay-off would be greater than Bushehr and the other reactor projects that were hinted at over the summer could offer.

But lingering mistrust over a number of broken US promises to Russia has caused Moscow to shy away from betting on Washington’s help, leading the Kremlin to prefer short-term cash gains to long-term economic bonanza with political strings attached. As one Minatom official summed it up to Bellona Web, “It’s better to have a bird in the hand than two in the bush.”

Indeed, it is estimated that more than 300 Russian enterprises are taking part in the Bushehr project, which has created 20,000 jobs. Besides, Russia has other lucrative contracts with Iran. Arms sales — always a hot item on world markets — to Iran are valued to reach at $8bn over the next decade, which would be twice as much as Moscow can expect in non-proliferation aid from Washington.

For the past eight years, disinformation has dominated news around elections all over the world. Despite this, it is still a widely misunderstood con...

A ruling by the European Free Trade Association Court that Norway’s continental shelf falls under the European Economic Area Agreement could dramatic...

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

Our December Nuclear Digest, reported by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center, is out now. Here’s a quick taste of three nuclear issues arisin...