Arctic Frontiers: Disinformation, Security and the Northern Sea Route

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

News

Publish date: November 11, 2014

News

AKHSHTYR, near Sochi, Russia – This settlement of some 160 people about 20 kilometers north of central Sochi heard hundreds of promises dating back to 2009 when the water dried up and the dust from its quarry started choking its residents and desiccating its crops.

The village lies at a crossroads between insane, inept bureaucracy and intense need, a middle ground straightjacketed by rigid, ludicrous officialdom whose single purpose seems the denial of any orderly structure of daily life.

Since Russia won it’s bid to host its subtropical Winter Olympics in Sochi, the village’s fate has also hung precariously from arbitrary rules established by distant Moscow deities to serve any community but Akhshtyr.

The deep hatchet blows shattering its mountainside landscape led to a round-the-clock roar of trucks toting limestone for Olympic construction. The bed jolting rumble of heavy machinery rolling up and downhill as more cement was quarried from the village’s namesake quarry kept residents up all night.

Olympic construction soaked dry the wells providing the village’s water as builders mixed concrete for a high-speed rail line and freeway between central Sochi and Krasnaya Polyana, where the Olympic alpine events took place.

The cost of the roadway alone was $8.7 billion – a price so high that Russian Esquire estimated the road could instead have been paved entirely with a centimeter-thick coating of beluga caviar.

Heavy machinery stomped on the landscape like an angry God, confounding water issues even more by driving the water table further down into the area’s famously porous geology, out of reach of wells. The arrival of toxic construction waste dumped in the quarry was yet another, but not terribly shocking, humiliation.

But all would be well if residents waited just a little longer, they’ve been told. And told. And told.

To wit: The cement from the quarry would unite them to the federal highway, reducing to minutes their access to Sochi – a nearly supernatural improvement.

The dust covering everything from the local persimmon harvest to residents’ lungs would clear up when the quarry closes. Gas lines would pump heat into houses running on wood burning stoves. New, deeper wells would restore drinking and wash water to their homes.

None of the promises were fulfilled.

Worse to come?

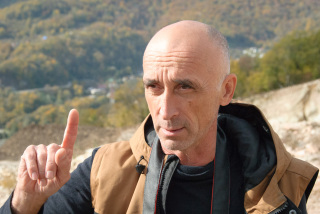

In fact, it’s likely the situation will get worse. Vladimir Kimaev of the Environmental Watch on the North Caucasus (EWNC) said the overwhelming presence of heavy machinery at the Akhshtyr quarry observed Monday shows it’s set to expand beyond its boundaries into Sochi National Park.

“If that happens, and it looks like it will, we will not forgive it,” he said, casting a bitter gaze over the vertiginous lacerations in the hills.

Russian Railways, which built the high-speed railway and much of the Olympic infrastructure had illegally dumped waste at Akhshtyr. Kimaev says most of that has been hauled away to other landfills, but there’s no documentary proof about where it ended up.

EWNC has also documented a total of 1,500 illegal landfills throughout the Krasnodar Region, where Sochi is located. Bellona documented numerous other roadside dumps of construction trash while in Sochi last February.

Toxic landslides of construction was have also avalanched into the Mzymta River, one of Sochi’s two main drinking water sources, raising the question of whether the river will ever be rehabilitated.

Kimaev and his EWNC colleagues have also headed up roadblocks, which as recently as two months ago turned away three semi trailers full of Olympic construction offcast headed for Akhshtyr – where dumping was supposedly officially ceased three months before the Sochi Games opened.

Meanwhile, there’s still plenty of evidence underfoot that Akhshtyr holds a fair share of Sochi’s construction rubbish.

Illegal expansion of Akhshtyr likely on horizon

Kimaev traces the fundament of newly packed gravel high above the valley bellow, which supports the weight of 14 KamAz dump trucks and land movers and traces the beginning of a crack.

Digging his sneaker toe slightly into the loosely packed fissure, Kimaev motions toward towering high tension electrical cable lines running right through the quarry – directly in the path of what he estimates is a cement and gravel avalanche waiting to happen.

“This, the trucks, all of it, right into the valley and onto the electrical cables with the next mild rain,” he says, musing aloud. “And more dust and the remnants of whatever dangerous construction waste is still under this stuff.”

What further construction plans could possibly be on the drawing board following the Olympic drive are unclear. Sochi’s hotels and executive apartment buildings stand half empty at best. Power stations bellow unneeded heat into fallow, drafty stadiums.

The remaining mounds of gnarled construction waste – the more toxic of it shoved into Akhshtyr’s half-closed caves – looks like it will be put to use as road foundations for more digging cranes, said Kimaev.

“So, we’re looking at more destruction, more dust, more strain on the Myzymta river,” whose now-poisoned rapids run right below the mouth of the quarry, dozens of meters below, said Kimaev. “More of the same.”

Village turned ‘Olympic Gulag’

Eight months after the Olympics – and five years after Akhshtyr’s wells were good for nothing but hollow echoes – the village has fully adapted to living in the 18th century.

Water is only available when it rains, which lately it hasn’t.

Bogos Antonyan, 62, Akhshtyr’s avuncular elder statesman, points out an elaborate concatenation of gutters he’s rigged across his roof to fill a 100-liter tank as he prays for rain. It’s a roof that, like most in town, shelters him, his wife, children and grandchildren, so that’s a lot of drinking and washing that’s not happening.

“None of us have showered in days, so apologies for any odor,” he says with characteristic literal – and figuratively dry – humor. He would offer his visitors tea, but that water will be needed for dinner, and it’s only yet turned noon.

“Regional and district officials drop through regularly to say they’ll be drilling deeper test wells to get our water supply back, that a paved road will connect us to the highway,” he said. “The faces change, but the lies stay the same.”

The numbing recycling of falsehoods has continued for so long that no one even bothers to complain about it anymore, he told Bellona. But everyone feels the pain: The highway that would unite the village to civilization is just a few kilometers away, and water could be restored if only someone in a position of power cared.

The newly minted Olympic federal highway cuts through the path that villagers had relied on for years to reach the old road running between Sochi and Krasnaya Polyana.

That road was where Akhshtyr’s children caught their school buses and residents would catch public transport to work or do the shopping. Regional authorities installed a pedestrian crossing under the high-speed rail line, but forgot to build a safe passage across the federal highway.

The only direct road connection to the outside world from the village has to be traversed by car – something that less than half of the community’s 56 households own, said Antonyan.

The narrow, white-knuckle road through the switchback hills adds up to about a two hour commute into Sochi for work or school.

Another fumbling effort by authorities has been water delivery. Too sporadic to be counted on, a truck sometimes trundles into town with barrels of water insufficient for most purposes, especially in the summer when gardens providing food for personal consumption and sale – one of the village’s main income sources – need to be watered.

“We are living in an Olympic Gulag,” Antonyan said. “We see there’s some very good meat next to us, but we can’t eat it.”

As anemic as the government’s efforts toward Akhshtyr have been, Antonyan maintains a jocular attitude toward the bumbling incompetence that may just as well exile his village to the moon.

“We understand that it’s hard for the government to understand, and we who live here love Russia – and because it’s Russia, we understand they will keep on lying,” he said.

Further down Akhshtyr’s death-trap road, the law takes another existential bend.

Fluid eco legislation creates Olympic homeless

Inasmuch as the Russian state stripped areas of the Sochi National Park of their protected status to accommodate filthy construction, the sword cuts both ways, allowing the state to appropriate private property by declaring it a national park.

Legislation in Russia allows for certain kinds of construction in national park areas for purposes of recreation, and this occurred on a massive scale along the banks of the Mzymta River, along whose beleaguered banks the Olympic freeway and high speed railroad run.

As such, one early morning in 2009, 53-year-old Alexander Koropov and his neighbors were told by a group of district administrators that their homes and farms were no longer theirs. They were now strategic territory to support the building of the high-speed rail and the caviar highway.

The government said it would give him about a half million rubles for his 3,600 square meters of land. The government then welched on the offer.

Koropov received the land and farm, which he’s lived on and worked for 25 years, during Boris Yeltsin’s voucher program that declared the property his. Now Yeltsin’s successor could rip it out from under him – his 35 cows and numerous dogs– for any reason at all.

His small farm consists of a persimmon orchard, a tumble down barn, a moonshine still, and stacks of firewood – all items of trade value to augment his $200 a month pension.

Earthquake of construction

Immediately after his land was seized, a gravel road was forged through his plot, literally a half a meter from his house, to the banks of the Mzymta River for the near-constant stream of dump trucks, bulldozers and boring machines to pound 24-meter bridge pilings for the railway into the riverbed.

“The pounding was constant, 24 hours a day,” he said standing on the Mzymta’s now filthy banks. “The pile drivers and the trucks literally shook me out of bed every night.”

Thick clouds of dust churned up by the trucks covered his persimmons, making them unsellable and depriving him of a large portion of his income. The dust also piled up on his house and dried out his grazing land. Even today, his windows are covered with film to keep the ubiquitous white chalk at bay.

But the dust comes not only from the still fresh bridge pilings and the trains above – it also wafts down the valley from the Akhshtyr quarry.

During construction, Koropov took his complaints to anyone who would listen, which turned out to be few but for environmentalists. Thomas Bach, President of the International Olympic Committee ,visited Koropov’s property. But the IOC declared the issue – as it did in nearly every cases of alleged environmental abuse – to be Koroopov’s problem, and his alone.

Koropov was something of a media star during the Olympics, and became an unfortunate poster child for the property destruction wreaked by the Olympics. His often salty-tongued and sometimes antic rhetoric is therefore well practiced.

His self-characterization as an “Olympic bum” and declaration that “Either Putin dies or I die” as the solution to his dilemma may be somewhat overplayed by now.

But the seemingly moonshine inspired bravado takes a turn for the somber when he gets down to the real reason he’d like to save his farm.

“I want my son Anton to have something,” he said, “and I have nothing to leave him anymore.”

26-year-old Anton served in one of Russia’s elite military Spetsnaz units, and now works as a janitor. Koropov and his son have discussed his return to military service, but Koropov finally arrived at a decision that rules that out.

“I will not have my son risk his life for a country that will do what the government let the Olympics do to its people,” he said.

“That, in my opinion, is not a government worth defending.”

Bellona held a seminar on countering Russian disinformation in the Arctic at the Arctic Frontiers international conference in Norway

Our December Nuclear Digest, reported by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center, is out now. Here’s a quick taste of three nuclear issues arisin...

Bellona has launched the Oslofjord Kelp Park, a pilot kelp cultivation facility outside Slemmestad, about 30 kilometers southwest of Oslo, aimed at r...

Our November Nuclear Digest by Bellona’s Environmental Transparency Center is out now. Here’s a quick taste of just three nuclear issues arising in U...