The Bellona Foundation, working with industry and the government, hopes to see all political parties in Norway commit to a to new plan for carbon capture and storage (CCS) at the Mongstad gas-fired power plant.

At a press briefing arranged by the government on the earlier this month, Norway presented its plans regarding the gas-fired power plant being built in Mongstad in western Norway. The government and the Statoil, who will develop the plant, agreed on whether – and how – to build it so as to incorporate a system for CCS.

Norway’s conservative parties have said that they are not committed to ensuring such a plan. Bellonas leader, Frederic Hauge, hopes they can take a more rersponsive stance.

“We will fight any constellation in the Parliament that does not do its job when it comes to reducing CO2 emissions,” said Hauge.

Bellona pleased with political interest

The two centre parties, Venstre and Kristelig Folkeparti, have already said that they will not enter into any government agreement that does not incorporate CCS at Mongstad. Bellona supports these parties’ comments.

The Mongstad gas-fired power plant has long been at the centre of an environmental battle in Norway. Although Bellona wants the Norwegian Parliament to fulfil its plans for Mongstad, the Foundation is also says the plan should have been much stricter.

Bellona has insisted that it would have been possible for Norwegian oil and gas giant Statoil to put the new greenhouse gas reduction technology to work as soon as 2011. Instead, the government and Statoil agreed that the CCS technology would not be implemented until 2014. The delay has caused protests among environmental organisations.

At current, CCS technology is expensive, and the Norwegian government will be footing much of the bill for installing the cleansing technology at Mogstad.

But Bellona experts were quick to point out that with each new experience installing CCS technology, the process becomes far less expensive, as more is learned and applied to the next instance.

“We want to climb the learning curve to lower the cost of this technology,” said Hauge.

Norway’s Social Democratic party, Arbeiderpartiet, which constitutes pro-labour and industry social democrats, are anxious to see the Monstad plant completed and in business as soon as possible for the new labour possibilities it will provide. The green parties, which are dominated by the Norway’s Socialist Left, or SV party, take a more environmentally friendly stance and have insisted the Mongstad plant not go on line until it can incorporate CCS. They have had to compromise, saying that CCS in the future is better than no CCS at all.

How committee are the Norwegian Government and Stateoil?

Aside from when CCS will become a reality, another central questios is how committed the government and Stateoil are to fulfilling CCS plans for Mongstad.

Central decisions about financing CCS will first be made in 2012. Government subsidies will cover a large percent – but not all – of the expenses associated with installing CCS technology. Statoil’s strong leverage with the government, therefore, has helped push back CCS installation deadlines imposed by the current authorities.

Hauge has expressed his dismay, noting that 2012 is a long time off – especially in financial and political terms – and that much could happen to disrupt the plans between now and then.

Time stretches out for Norwegian CCS

Of special concern to Hauge is the fact that between now and 2012, two new parliaments – which may have very different priorities than the current one – will pass through the halls of Norwegian power and possibly scuttle the investment plans in CCS, which only prolongs the period Bellona and other environmental groups will have to struggle on behalf of government-subsidised CCS.

“Before to 2014 we will have to fight for 1,825 days to ensure that CCS will be a reality at all,” said Hauge.

“We have a long road ahead of us, more than two parliament elections between now and 2014, and because the investment decision (on CCS) will not be taken before 2012, a lot can happen during that time” that could change government spending priorities.

The silver lining, said Hauge, is that Statoil has actually committed itself to CCS purifying technology beginning in 2014. Nonetheless, he said, Bellona will continue to fight for the application of CCS at an even earlier stage.

International applications

Nonetheless, the CCS facilities planned for Mongstad are almost immediately applicable to gas-fired power plans throughout the world, and the Mongstad plan can provide a blueprint for other gas fired power stations internationally, allowing for a global application of the process.

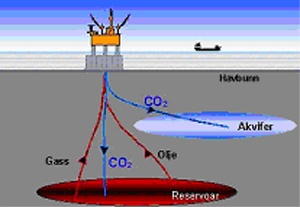

CCS is a method by which carbon produced by gas and coal fired plants can be captured and stored. This stored carbon then has commercial value to the oil industry, which can use the carbon gas for enhanced oil recovery by pumping it into oil fields to force out more crude – a process called enhanced oil recovery for which, among other things, natural gas is currently used.

The environmental benefit is then that the carbon is locked in deep repositories underground and does not enter the atmosphere. Putting the plan into action as soon as possible would provide a case study for the rest of the world on how a CCS infrastructure would work, allowing countries from Asia to the United States a view on how the adaptable technology is in reducing greenhouse gas output at even the oldest gas and coal fired plants.

Statoil pressure wins the day

But Statoil has managed to put CCS on the back burner for now with its powerful leverage in Norway’s political and industry decision-making circles.

The fly in the Mongstad ointment, noted Hauge, was Norwegian oil giant Statoil’s full-court press on authorities to sink more rapid and more comprehensive capture plans – which is very much to Statoil’s financial advantage.

“Now Statoil can do whatever it wants,” said Hauge.

Bellona blamed Norwegian Minister of State Jens Stoltenberg for inaccurately assessing how soon CCS could be in place. Stoltenberg asserted that it will not be ready for application until 2014. According to Hauge, CCS could have been in place much earlier if only the lobbying power and the resources had been available to environmentalists.

The year 2014 for application of CCS technology is an arbitrary deadline controlled by Statoil, said Hauge, as the government could easily have chosen a more rapid timeline to have the technology in place.

“In spite of everything, it is not easy to explain that they will be building a full-scale purification system in Kårstø five years earlier (than at Mongstad), and assuming that capture will be in place at Tjeldbergodden by 2011 or 2012,” said Hauge.